Lawrence Medal ‘13, bachelor of architecture ’74,

master of architecture ’78, master of arts (Asian Studies) ‘78

Devoted to preservation of historic built environment

When David Lung's watch beeps during a morning meeting in Eugene, he apologizes and remarks, "My watch is still on Hong Kong time. It's 1 a.m., my bedtime." The fact that Lung needs an alarm to remind himself to shut down for the day illustrates his approach to preservation architecture: It's all-consuming, seven days a week, eighteen+ hours a day (another alarm wakes him around 6:30 a.m.).

Lung, BArch '74, MArch '78, serves as the UNESCO Chair in Cultural Heritage Resources Management at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) in a dual appointment as Lady Edith Kotewall Professor in the Built Environment. He is a prolific author with dozens of publications to his name, and was instrumental in bringing to fruition three World Heritage designations: the Historic City of Macao, the Kaiping Diaolou and Villages, and the Historic Cities in the Straits of Malacca.

A native of Hong Kong, Lung came to UO in 1970 to begin a bachelor's degree in architecture. The transition from Hong Kong to Oregon was a culture shock, from the compact size of Eugene to weather nothing like the tropical climate he left behind.

Above: David Ping-yee Lung, 2013 Ellis F. Lawrence Medal recipient.

"As a young student coming from a densely populated city of Hong Kong to a rural area called Eugene, Oregon, I arrived thinking that I had to go home armed with the ability to design high-rise, iconic buildings, not knowing that in Eugene eight to ten stories is a high-rise. So I wondered if I had come to the wrong place to study architecture. I came at a time when the school was poverty-stricken — I didn't even have a proper studio desk, just a plank of plywood sitting on two stools, yet I was paying out-of-state tuition. My first studio, they put me in a little wooden hut designed and built by students (the "Graduate Shelter") across the Millrace. The school was that poor. There was no heat in there and, not knowing Eugene weather, by November I was freezing cold. I thought, What am I doing here?"

But he stuck it out and grew along with the program. Nearly three decades later, in 2008 he established and funded the David Lung Design Prize in Architecture at UO, an annual scholarship. In 2000, he donated funds from his private practice (with two other teachers) to help start a heritage architecture program at HKU. Most notably, he has taught hundreds of architecture students, sharing with them the lessons he learned at UO that changed his philosophical outlook.

"I really owe my whole life career to (the University of) Oregon," he says. "What Oregon did for me, it's not so much just about the education I received here, it is the whole value that Oregon preaches – it is a value of the intellectual inquisitiveness, it is the value of searching for one's own identity, it is the value of respecting other people, in particular, their ethnic and cultural differences. It was the first time in my life that I had come to contact and made friends with so many different nationalities from all over the world."

During his final year at UO, Lung says, he "began to realize there was this theoretical aspect of design that we should take care of, that there were social, cultural, political, economic factors to architecture design." He especially points to (the late) Professor Bill Kleinsasser's class "Experiential Learning," which shared philosophy from the book The Oregon Experiment, by Christopher Alexander. Alexander's book was based on research on the UO campus that concluded design should shape places to nourish people holistically, that users of buildings should participate in their design, that the community should have more control over its environment.

Exposure to this in his UO coursework and studios, Lung says, helped open him up "to other intellectual challenges beyond designing iconic buildings. It was Alexander's idea of a 'timeless way of building' that turned me on," he says. During spring term of his fourth year, Kleinsasser encouraged Lung to apply for a prestigious summer internship with the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in Washington, D.C. He won one of just four slots. "That was a life-changing experience, because after coming back from Washington, D.C., then I knew there were strong theories, different approaches to thinking about architecture." He was 23 years old.

"Back in Oregon after my internship, I began to explore architecture apart from high-rises and iconic buildings. I realized there were other aspects to architecture than what I thought architecture should or shouldn't be: There is indigenous, the nameless, the primitive, the vernacular, that I begin to take interest in. I began to look into the wooden houses in Eugene."

From then on, he focused his intellectual curiosity "on something I'd never thought of as being architecture before, and that is the study of vernacular." Lung graduated in June 1974, the height of the Mideast oil crisis and its debilitating effect on the U.S. economy, when the only job he landed was with a small firm doing work "that bored me to death. So I began to think of going to graduate school." Lung wanted to apply "back East, at Harvard or Princeton, but (his UO mentor and then-dean) Bob Harris told me, 'No, no, no. Those schools are not good for you. Would you consider Oregon?' "

The title of Lung's subsequent UO graduate thesis, Heaven, Earth and Man: Concepts and Processes of Chinese Architecture and City Planning, hints at the transition Lung would make between his first year as an undergrad longing to design skyscrapers, to the heartfelt attention to heritage preservation he had grown into seven years later. He noticed the shift in himself when he returned home to Asia after school.

"When I went back to Hong Kong in the late 1970s and early '80s I began to think how to preserve vernacular architecture because development was quickly destroying the region at a fast pace. So I started to look into preservation techniques," which turned out to be a mostly solo enterprise because almost no one else was skilled or interested in the concept. In 1989 he was asked by the government to join the Antiquities Advisory Board, a relatively new national committee. After just two years he was appointed chairman, "which gave me a lot more freedom" to move his preservation agenda forward.

The year 1997 saw the changeover of Hong Kong's sovereignty from British to Chinese. As head of the antiquities board, Lung promoted "a Year of Heritage, a full year of events, fifty-two, one per week — exhibitions, conferences, opening of heritage trails, concerts in heritage buildings." He also organized an international conference, "Heritage in Education," which he followed up in 1999 with the conference "Heritage and Economics." It was there that he met "several people who would eventually help me to set up the heritage program at Hong Kong U in the year 2000."

Just thirteen years later, the program is burgeoning. In 2012, the school's Architectural Conservation Programme (which Lung also launched) introduced a bachelor of arts in conservation covering the multidisciplinary nature of architectural conservation from single buildings to historic districts, and including "the wider social context."

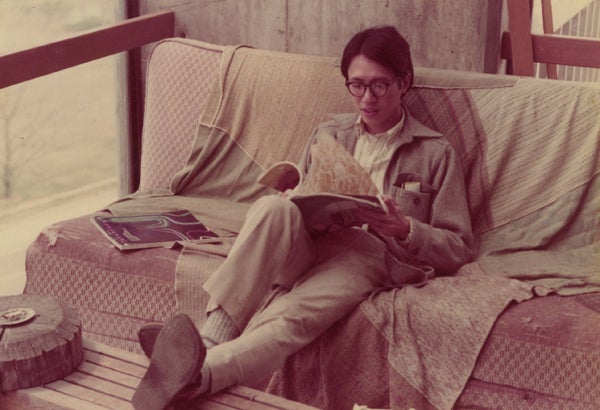

Above: David Lung in Lawrence Hall, circa 1970s.

Lung began as a lecturer at HKU in 1984 and was promoted to full professor in 1993. In 2011, he became dean of the faculty of architecture. HKU has recognized him with the Faculty Outstanding Teaching Award (2010), Long Service Award (2009), and Research Output Prize (2007). He was a founding member of UNESCO-ICCROM Asian Academy for Heritage Management, a network of institutions throughout Asia and the Pacific region that offers professional training in the field of cultural heritage management. Active in public service, he has served on the Council of the Lord Wilson Heritage Trust, the Land and Building Advisory Committee, the Environment and Conversation Fund Committee and others. From 2009-11, he helped secure world recognition of Sai Kung Geo-Park. In 1999, he was awarded the Silver Bauhinia Star (SBS) by the regional government of Hong Kong to recognize his leadership roles in heritage conservation.

His other honors and distinctions include Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE, 1994) for designing housing for the underprivileged elderly, and service as vice president of China ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites).

In view of his active participation in the built environment, he also was made fellow of the Hong Kong Institute of Architects, a fellow of the Royal Institution of the Chartered Surveyors, and an honorary member of the Hong Kong Institute of Planners.

In addition to teaching and developing new curricula at HKU, Lung is working with faculty members at UO and HKU to gain accreditation for an architecture program at Zhuhai University, a private college in Hong Kong, and on teaching online heritage architecture courses through Edx beginning fall 2014.

Above: One of the sites that Lung is responsible for listing as a World Heritage Site is the Central Market in Macau.

Lung attributes his achievements to the lessons he learned at UO. "I started off my education here at Oregon with the wrong assumption (that he needed to learn to high-rise design), but I came with an open mind. With hindsight, the education I received was a very balanced one. I came away with an education balanced in technology as well as culturally, intellectually challenging subjects. I still remember the valuable lessons I learned from John Reynolds on environmental control systems, from Don Peting and the late Mac Hodge and Steve Tang on structures, from Bob Harris, Jerry Finrow and Bill Gilland on design theories and methods, and from Don Genasci and the late Marion Ross on history and theory. That's why today I am able to carry out all the things I've done the past thirty years."

In June 2013, Lung was presented with the Ellis F. Lawrence Medal, the highest alumni honor presented by UO's School of Architecture and Allied Arts.

"As an architect, university leader, historic preservation expert, and educator, David Lung's professional achievements are outstanding and inspiring," A&AA Dean Frances Bronet said in announcing the award. "He is deeply devoted to his students, his university, and his profession as well as his alma mater. Throughout his career, David has pursued scholarship in historic preservation and conservation practices and has gone the next step and guided public policy on a national and international level. We are honored to include David as one of our own alumni who can inspire our school."

Lung says he, in turn, was inspired by UO. "What I got out of Oregon was not only the knowledge my teachers shared with me but of lifetime values — the integrity, the honesty, the way to do research. And social values, the value of selflessness, of helping each other, that kind of spirit that I've taken from you that must continue elsewhere in the world. I'm awfully grateful, truly grateful, for what I learned here. I never thought a place could develop someone to almost endless opportunity. I hope I've kept these values and can transmit them to my students at Hong Kong U."

Given his legacy, which will self-perpetuate through his legions of students and their students in turn, those values are most certainly being passed on.

Above: Lung oversaw the Kwun Tong urban renewal project. Photo courtesy URA HK.

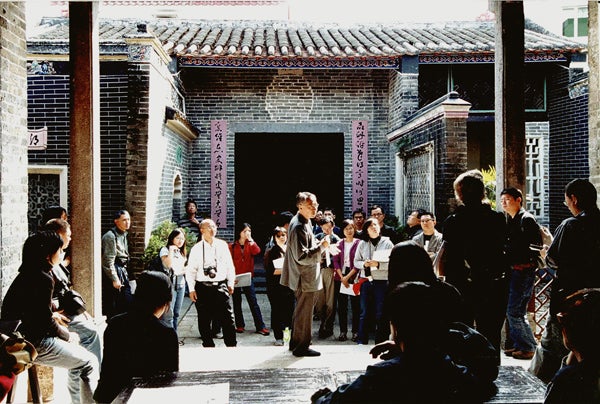

Above: In 2000, Lung founded the Architectural Conservation Programme, an in-service post-graduate degree course in architectural conservation, which has since been responsible for training most of Hong Kong's current generation of conservation professionals. He's pictured here teaching a class.

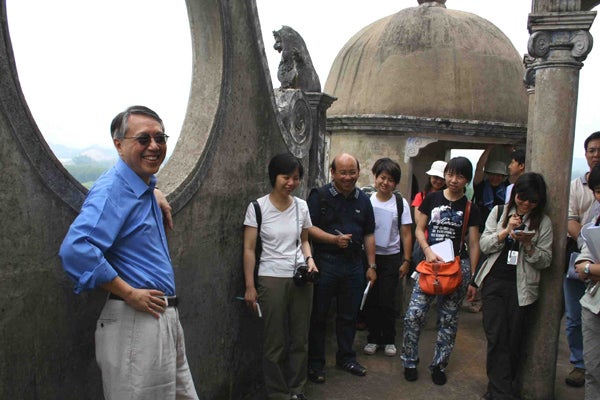

Above: Lung leads a field trip with students.