The art and design village across from Franklin Boulevard has been the home to many programs of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts since the 1960s and is still an active hub for creative practice. Seven media areas for the Department of Art have studios, faculty offices, and graduate student workspaces on the Northsite. These media areas are sculpture, ceramics, painting, photography, digital arts, fibers, and metals and jewelry. In addition, the Northsite provides space for teaching and research in architecture, interior architecture, product design, and the Urban Farm.

Much of the current feel and presence of the Northsite is due to the Millrace I and Millrace II buildings added in the mid-1980s and later buildings constructed in the early 1990s. However, the school had the Northsite as a key location starting in the 1960s, and it has evolved over time into a vital center for many programs.

Above: The Millrace I, pictured in 1986 after its recent completion, helps anchor the Millrace complex. Image courtesy Bill Gilland.

In this story, we will trace the development of buildings and programs that call the Millrace and Northsite complex home. The site now includes the current cluster of nine buildings and the Urban Farm outdoor classroom.

Much of the history of the development of the Northsite has been framed by the need for additional studio and research spaces that could not be accommodated at the Lawrence Hall site. The site’s evolution into an active teaching and studio hub took decades to mature. And its development has been touched by some dramatic controversies as well.

In 1960-61, enrollment in the School of Architecture and Allied Arts was 337 students. By 1970-71, enrollment grew to 1,469 students. The need for space was a pressing issue for the school and university administration. Beginning in fall 1966 and throughout 1967, there were numerous discussions about facilities planning. Many of the most controversial issues played out in the school newspaper, the Oregon Daily Emerald.

Above: The four-story addition to Lawrence Hall was completed in 1971. Photo courtesy Bill Gilland.

The Lawrence Hall addition project was fifteenth on the State Board’s list for approval in the 1967-1969 biennium. Dean Walter Creese noted, in a story published January 19, 1967, that there were “unlimited demands on limited resources.” The State Board authorized $1,645,000 for the project and, Creese reported, “the architects thought that it would require five or six million dollars to build the building we need.” The school considered this the first phase of a two-phase project and was hoping to double its available net square feet from 50,000 to 110,000 after completion of phase two. Creese said to the Emerald writer in January 1967 that “the school needs space now.”

The architectural plans being considered proposed adding a four-story addition to Lawrence Hall along the University Street side of the existing building. The addition would require the demolition of art studio spaces. Jack Wilkinson, head of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts, felt that action would cripple the instructional programs in the arts during construction and the replacement space would not meet the needs of the growing program.

Wilkinson was a passionate advocate for the art programs and their role in providing courses open to any university student. To make matters more difficult, the addition to Lawrence Hall was sited on unstable soils that would require the added expense and effort of adding a structural piling foundation to support the concrete building addition. These additional costs also limited the options for construction of the new space that the school needed.

The State Board and University of Oregon President, Arthur Flemming, wanted the school to stay at the Lawrence Hall site. “There are not many universities which have art and architecture together, as the university does,” he said, adding that keeping the two together was “educationally beneficial” to UO. But the reality of budget and space for two major studio-based programs was another matter.

The struggle eventually led to delays in the building plans on the Lawrence Hall addition and the reassignment of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts to the College of Liberal Arts by President Flemming. The art faculty and Wilkinson requested this reassignment with the support of Dean Creese in early 1967. Later, in 1968, the Emerald reported that the agreement was provisional in that the State Board of Higher Education had not officially transferred the department out of the school. However, the head of the department reported to the UO’s Dean of Faculties and not the dean of the school. The department returned to the school in 1970.

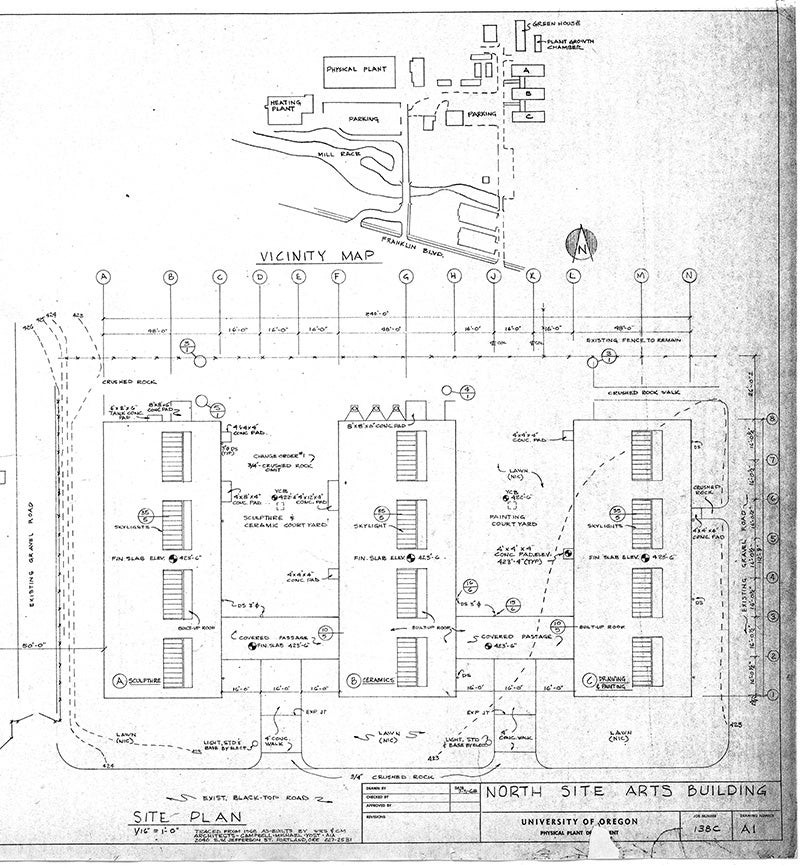

Around the same period, as the school worked to maintain momentum for the capital construction project, the entire school faculty—including fine art faculty members—unanimously approved a compromise proposal as a solution to the issues. They voted to expand the school on the present site of Lawrence Hall and “investigation should be given to the possible provision of space for some activities of the school on other sites,” according to the Emerald on January 20, 1967. This led the way for the development of the area across the Millrace. The drawings for fine arts studios on the Northsite were produced in 1968, led by project architects Campbell, Michael, and Yost along with draftsmen at the UO’s campus planning office.

Above: The massive timber frame kiln shed was designed and built by architecture students beginning in 2000, led by Professor Stephen Duff. The exquisite structure covers the wood-fired kiln. Photo by Jenerik Images.

The first of three Fine Arts Studios—A, B, and C—were constructed in 1968 as temporary buildings because there was anticipation for later capital construction phases for the school’s facilities. Building A is the home of sculpture, Building B houses ceramics, and Building C was originally the home of painting and is now the studio for metals and jewelry.

During the 1970s there were Quonset huts on the Northsite that housed art studios for fibers, faculty offices, and graduate student work spaces. Barbara Pickett, associate professor emerita, remembers the Quonsets 121, 123, and 124 as the studios for fibers. The Quonset with “dome” or arched roof housed the weaving studio and the other smaller square building housed the dye lab. “We were the classroom on the frontier,” Pickett says. She recalls that Professor Max Nixon, who also taught metals and jewelry, advised her as a new faculty member to take up space on the Northsite because it “would be safe and no one will lust after it.” Pickett says that the fibers program relocated from Lawrence Hall to the Northsite around 1978 and eventually moved into Millrace I in 1991-2. The dye lab was incorporated into Millrace III. She laughs at the memory of their frequent challenges of working on the Northsite, which the artists dubbed the “art ghetto.” However, it was also a good location for art study. Pickett adds, “the Urban Farm was an incredible gift for the artists; it added a touch of nature.”

The Urban Farm began in 1976 as a productive landscape course and has grown into one of the most popular classes at UO. The inspiration for the farm came from Richard Britz, a new faculty member. He had done research in China and was moved by the fact that “every piece of arable land was used for food production,” explains his colleague Ann Bettman, adjunct career instructor in the department.

“He felt that it was a strong mission for landscape architecture to respond to, and took the lead in teaching spring term classes,” Bettman adds. Eventually, Bettman became the principal instructor for many years after Britz left the university.

The Urban Farm has been transformed into an outdoor classroom for the Department of Landscape Architecture. The 1980s was a rough period for the farm; staffing was limited and the ground was plowed under and lay fallow for some time. “The Urban Farm started to take off again in the 1990s,” says Bettman. This was a popular response to growing environmental awareness movement and similar courses offered at other universities. Bettman remembers enrolling 120 students in a class, eventually setting enrollment limits to 80 students. The department began to offer the classes in all seasons and the team-leader system was established to provide a strong operational structure to the program.

Adjacent to the Urban Farm is an orchard of fruit trees—pears, cherries, and apples—that was planted in 1978. Bettman recalls the planting of the Lynn Mathews orchard, a living memorial created to honor a former student of Britz and one of the farm’s most active students. The family was so moved by the spirit of the Urban Farm and the work of their daughter there, that they established an endowed fund in her memory.

Students in the Interior Architecture Program contributed the greenhouse to the Urban Farm in 1981-82. They designed it, raised materials and funds to build it, and did the construction. Bettman still considers it a generous gift that happened only because of student initiative. Minor changes have occurred on the greenhouse, with the addition of a shed and expanded eaves.

Above: The Greenhouse was a project of interior architecture students who designed, raised materials and funds, and built it for the Urban Farm in 1981-82. Photo courtesy Bill Gilland.

The Wilkinson House, originally called the Farm House, was the site for art faculty offices and housed a darkroom and printing press in the basement, with a classroom on the first floor and grad spaces on the second floor, according to Ken O’Connell, professor emeritus. “In 1978, when I joined the faculty my office was in Wilkinson House,” he says. The house was named in honor of Jack Wilkinson, a tribute that was led by a colleague and art faculty member, the late Professor Dave Foster.

O’Connell was head of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts in the 1980s and he recalls the next building project in 1989-91. “We tried as we may, but it was not going to happen that there was enough space in Lawrence Hall for the programs of art and architecture. So fine arts agreed to continue with two sites and a split faculty,” O’Connell continues. “The Northsite would be the more industrial location with sculpture, ceramics, jewelry and metals, fibers and as it turned out photography and a dye lab,” he adds.

The Millrace I and II buildings were built in 1986 The UO requires that any program displaced by construction be provided for in other new or remodeled quarters. When the Science Complex needed the land where Emerald Hall was located, the Millrace I and II buildings were constructed to accommodate the displaced architecture studios. According to Fred Tepfer, long time Eugene resident and project manager for UO Campus Planning, the buildings were built quickly and in use in 1986. The architecture studios housed in Emerald Hall found a new home in Millrace I and II. They stayed until 1991-92, when Physics could move into the new Science Complex and free up space in Pacific Hall. Once architecture studios moved back across Franklin Boulevard, the Millrace I and II buildings were remodeled to meet the needs of visual design, now digital arts, and fibers.

“I believe architecture left Millrace I and II when we were able to move into Pacific Hall. We had to wait for Physics to move out, and for the space to be remodeled,” recalls Michael Utsey, associate professor emeritus and former associate dean. “It took a couple of years, probably until 1991-92. Some of the physics labs had to be pried from the building.”

Above: The Millrace III is the fine arts space for photography, painting, and the dye lab for fibers. It was completed in 1991 and provided a northern edge to the new Millrace complex courtyard. Photo courtesy Office of External Relations and Communications.

Above: The courtyard between the Millrace buildings provides valuable open space for gatherings and temporary project space for the Department of Art. Photo courtesy Bill Gilland.

In 1987, the Oregon Legislature approved funding for the school’s Addition and Alterations Project. The project would eventually include renovations of space and new projects on the Northsite. In the past the Northsite was seen as a “backyard” of the university, where experimental and hands-on activity were located. The main focus of the project was to develop and extend the workshop character, taking advantage of the Millrace as a distinctive environmental feature and create a courtyard and village-scale complex.

Major funding for the new construction on the Northsite in the project included the ceramics barn for kilns and storage, the Millrace III building for advanced painting, photography and the dye lab for fibers, and the woodshop. The construction took place in 1990-91 after a period of redesign. According to Ron Graff, associate professor in painting, the department now can say “we have the most spacious, light-filled studios of any graduate program in the country.”

The Woodshop was constructed to support furniture design and woodshop needs as well as building technology research space. The Woodshop building was completed in 1991-92. It was constructed on land that had been part of the Urban Farm garden. The Grad Shelter that was built on the Northsite in 1965-68 served as the woodshop facility for many years. It was removed when the new Woodshop was constructed.

Above: The Woodshop is located between Fine Arts Studio C and the Urban Farm. It was completed in 1991. Photo courtesy the Office of External Relations and Communications.

Shortly after the completion of the new buildings, a Department of Landscape Architecture construction course led by Professor Cynthia Girling, in 1992, refined the north edge of the Urban Farm. The project included a retaining wall, fence, gateway, stairs, and entry walkway. This work solidified the Urban Farm’s permanent role as an outdoor classroom.

Other significant projects on the Northsite include several design-build projects including the glorious kiln shed constructed from 2000-10 by Stephen Duff, associate professor of architecture, and his legion of students and other contractors.

The Millrace 4 building across the footbridge near the Urban Farm is used for product design and art faculty offices, classroom space, and studios. It is the latest addition to the Northsite complex.

Sources:

• Interviews with Ann Bettman, Michael Utsey, Ken O’Connell, Fred Tepfer, Don Peting, and Barbara Pickett

• Visual resources provided by Ed Teague from the Stan Bryan collection • Digital Resources Collection, UO Libraries

• A&AA Collection, External Relations and Communications

• Campus planning archives provided by Christine Thompson, UO Campus Planning, Design and Construction

Above: The Fine Arts Studios A, B, C were constructed as part of the school’s addition project in 1968. Image courtesy A&AA Library, Stan Bryan Collection.

Above: Site plan for Fine Arts Studios A, B, C in 1968. Image courtesy UO Campus Planning office. Click image to enlarge.