bachelor of landscape architecture ‘39

From public works to private residences, Erfeldt a ‘visionary’

Oregon’s lush natural spaces have long been a trademark for the state, its lush greenery often serving as a point of pride in the hearts of Oregonians everywhere. One UO alumnus, landscape architect Arthur Erfeldt, helped to shape many of Oregon’s most iconic places in years past, many of which have lived on into the present day.

Born in Boston in 1909, Erfeldt was a visionary and a pioneer in the field of landscape architecture. His lifelong dedication to the study of the interaction between humans and the natural spaces we surround ourselves with led to the creation of some of Oregon’s most beautiful outdoor areas.

Above: In 1950, Erfeldt designed the garden of Florence Lynch, a client with whom he and his wife would become close. His designs for the Lynch House are among many of his works now on the National Register. Here, Erfeldt and Florence Lynch pause after walking in the Lynch Gardens; note Erfeldt’s rolled-up pant cuffs and muddy shoes.

After settling with his family in Oregon at age nine, he attended Washington High School in Portland. Erfeldt then went on to pursue the study of landscape architecture, first at Oregon State University then transferring and finishing his undergraduate studies at the University of Oregon. He graduated in 1939 with a bachelor of arts in landscape architecture, which at that time was still a relatively small program.

When the United States became involved in World War II, Erfeldt went to work with the Army Corps of Engineers at Boeing, where he built airplanes for the war effort. While at Boeing, he met and married Flora Burkhardt, whose family owned and ran popular plant nurseries and florist shops in the Pacific Northwest. The couple went on to spend the rest of their lives together, becoming pillars of a growing Portland landscape design community and fostering numerous influential friendships along the way.

At the end of World War II, the Erfeldts moved to Stockholm, Sweden, for both a new adventure and the completion of Arthur’s graduate studies at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. While there, he studied under and worked alongside one of Sweden’s most prominent landscape architects, Baron Sven Hermelin. On top of a demanding course load, Erfeldt also designed numerous public and private gardens for the citizens of Stockholm, helping to establish his name within the international landscaping and architectural community.

After finishing school in Stockholm, the Erfeldts returned to America in 1948, settling in Portland. Arthur opened a landscape architecture firm of his own in the Concord Building (which was placed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977).

For thirty-two years, until his retirement in 1980, Erfeldt worked in Oregon, designing many private residential gardens as well as gaining praise for his large public works. Notable among his residential spaces were those designed for Barbara Sprouse, Mrs. Phil Miller, Roger Meier, the Grossman family, and the J.K. Gills. His designs for Lincoln High School and First National Bank’s Stadium Branch earned him widespread admiration, as did his master plan for the Bush Pasture Park in Salem. Multiple residences featuring Erfeldt’s landscape designs have been included in the National Register of Historic Places, often with special emphasis placed specifically on his contributions to the spaces being showcased. In 1950, he designed the garden of Florence Lynch, a client with whom he and his wife would become very close. His designs for the Lynch House are among those placed on the National Register.

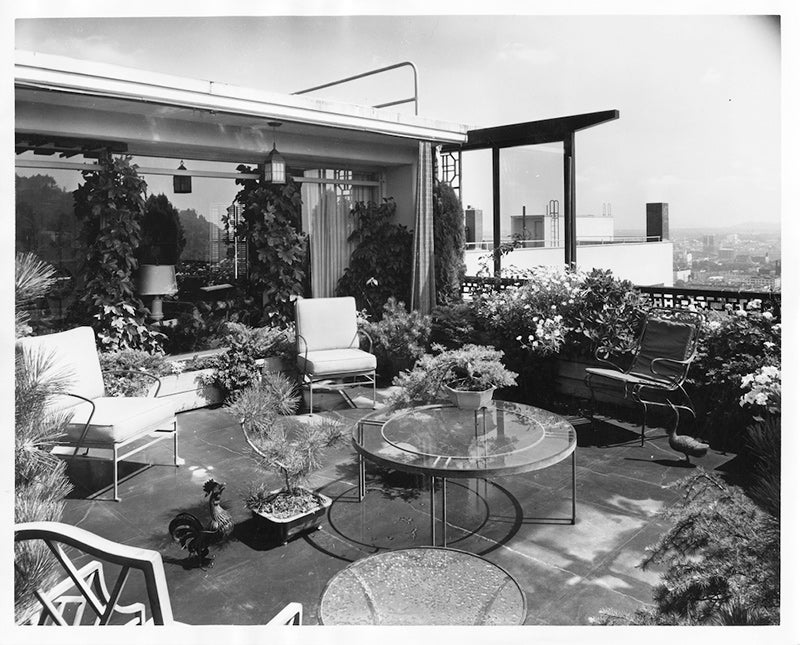

Above: The Portland Roof Garden, an Erfeldt design, summer 1957. Landscape architect Wallace K. Huntington described Erfeldt’s work as “invariably stylish,” praising him and noting that his seamless blending of Swedish and American design styles made him important both in the U.S. and abroad.

Erfeldt was also the recipient of a wide variety of awards and recognitions, frequently being rewarded for his outstanding conceptual designs. His work was also featured in many publications, such as Sunset magazine, The Oregonian, Better Homes and Gardens, and House and Garden.

In an essay on landscape architecture in the Northwest, fellow landscape architect Wallace K. Huntington described Erfeldt as “one of the few Occidental designers sufficiently versatile to handle the traditional Oriental motifs with the same skill as the European formal tradition. … He created a harmonious blending of rock and foliage, water and sand, so much in the Oriental manner that one might think momentarily that the distance of Mt. Hood was in truth Fujiyama.” Huntington also described Erfeldt’s work as “invariably stylish,” praising him and noting that his seamless blending of Swedish and American design styles made him important both here and abroad. When searching for inspiration and escaping allergy season, the Erfeldts frequently traveled to places such as Central and South America, Europe, Bermuda, and various parts of Africa.

The UO Knight Library Special Collections houses many of Erfeldt’s files, including awards, photographs, design sketches, postcards, and other items that can help to illuminate his design philosophy for those interested in preserving his ideas.

When Erfeldt finally decided to retire from his firm at the age of 71, he continued to maintain his home and 40-acre sheep and cattle ranch in West Union, Oregon. He died May 25, 1993, leaving behind both his wife, Flora, and a lasting design legacy. The Arthur and Flora Erfeldt Endowment, for the benefit of the UO School of Architecture and Allied Arts, was generously created to honor the memory of their tireless work and passionate vision for the future.

Above: Erfeldt designed the Oregon Centennial East Plaza for the 1959 Centennial Exposition, at the time the largest fair in the West since the San Francisco World’s Fair of 1939. The expo ran June-September 1959.

Above: The entrance courtyard to the Portland Federal Savings Bank, another Erfeldt design.