bachelor of architecture ’13

Recent graduate puts focus on climate-adaptive design

Following a busy post-graduate trajectory, an alumnus of the Department of Architecture has narrowed his sights on adaptive design for climate change.

William Smith is described as a “wunderkind” by A&AA Acting Dean and Associate Professor Brook Muller.

William Smith is described as a “wunderkind” by A&AA Acting Dean and Associate Professor Brook Muller.

“In his time here, he was an intellectual leader who contributed enormously to the A&AA learning community,” says Muller.

Smith has also garnered praise from Professor Howard Davis, whose studio Smith attended.

“He is committed to responsibility with respect to the environment, and strongly believes that architects can make a difference in fixing our world,” says Davis. “Will exemplifies what our school is about—socially and environmentally engaged, comfortable with and eager for collaborative work, intellectually generous.”

During a summer abroad in 2012, Smith interned with haascookzemmrich STUDIO2050 in Stuttgart, Germany. Smith met with UO peer Dylan Woock in Berlin; the two reflected on the special opportunities A&AA had provided them, and wanted to return the courtesy by contributing to the school. However, each only had a year left of school, and options were limited.

“From that conversation we decided the best way we could engage the school beyond our own work was HOPES [the Holistic Options for Planet Earth Sustainability conference],” Smith says. “Through it, we hoped to elevate the latent knowledge and discourse held within Lawrence Hall.”

Student groups had organized the eighteen previous conferences. As HOPES student director in 2012-13, Smith found the main challenge was cutting through the ambient noise of Lawrence Hall to generate excitement for the event.

Eventually, he arranged three workshops and six panel discussions, involving six panelists and eight guest lecturers.

“Once speakers were solidified I think the student body started to see that something special was going to happen, and by the time the conference started we had a great turnout,” he says. “I saw a lot of excited people, both students and professors.”

Smith found that his idea of sustainable design had changed while studying architecture at UO.

“Whereas I had started at the university thinking that sustainability meant [photovoltaic] panels only, by the end, I realized that architecture can be involved in its ecological context in many deeper ways,” he says.

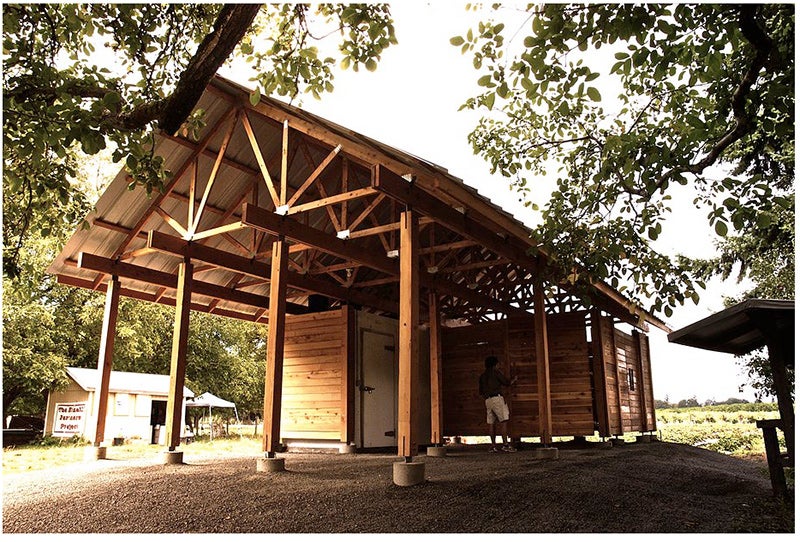

Smith finds himself regularly thinking about two student projects he participated in. One was with designBridge, a student-led program that builds projects for local community groups. Smith contributed designs for an organic farm north of Eugene, where immigrant farmers needed a flexible and deconstructable structure, so they could move it when needed.

Above: Smith worked on “The Small Farmers Project” as a student in UO’s designBuild organization. His team designed a deconstructable barn that can be disassembled and moved. Photo courtesy William Smith.

The second student project he often thinks about was part of a design for an outdoor school on a small island in Malaysia. Due to extremely limited funds, the majority of the school, Mantanani Conservation School, was built with reclaimed materials including driftwood from the ocean.

“This work embedded within me a belief that successful architecture can be affordable, of its context, and ethically charged,” he says. “I really look forward to seeing how both of these projects continue to age due to their environment and change through intense use.”

Following graduation, Smith landed an internship with Allied Works, a firm based in New York City and Portland. He worked on a number of projects and competitions and engaged in formal conversations about how architecture can organize itself based upon internal and external influences.

“I was lucky enough to make a couple of concept models like the ones I gawked at while in school,” he says. “My role was to be a young designer that produced tectonic ideas.”

Today, he is the youngest team member at the Architecture Research Office (ARO), another New York City firm, where his responsibility is to generate raw designs to be analyzed as a group. Through this process, abstract issues are solved through design.

Above: A structure for Mantanani Conservation School, on a small Malaysian island, was built from salvaged materials. The school was one of Smith’s projects as a student. Photo courtesy Arkitrek.

One of Smith's current projects is a farmhouse built on a 75-acre site in Connecticut that is being converted back to a wetland. Through collaboration with Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Inc., the site will include a new house for the current residents. Smith says the project overlaps both environmental and agricultural needs, as well as family celebrations.

Another of Smith's project at ARO is the design of a public boathouse for Brooklyn Bridge Park. Smith says the project will be the only boathouse in the park. Issues of extreme flooding and changes in sea level have been challenges for the designers.

“If the way we live in this world must change,” he notes, “our architecture should facilitate that change in a way that elevates our experience as well.”

Smith says he is learning that working for some of the world’s more famous firms does not equate to becoming the best designer, that rather self-directed inquiry along with being part of a diverse team can lead to the greatest growth in abilities. He relates this philosophy back to his time in UO architecture studios, when he found collaboration with his studio’s peers inspired the most productive and innovative workplace.

“My experience in Lawrence Hall made it clear that with a meaningful goal, determination in learning how to achieve it, and a group of great people with you,” he says, “it’s possible to achieve something most likely better than what you initially imagined.”