bachelor of architecture '32

‘I’m an architect with a capital A.

Being a woman has nothing to do with it.’

Chloethiel Woodard Smith was an extraordinary woman who lived an extraordinary life. Considered a trailblazer for women in architecture, Smith got her start at age 12, when her family built a house for themselves in Peoria, Illinois. She was forever hooked on creating new and beautiful spaces in the world.

A member of the UO graduating class of 1932, Smith was one of around 150 students in the School of Architecture and Allied Arts during Ellis Lawrence’s time as dean and W. R. B. Willcox’s time as head of the architecture program. The presence of these two men in her undergraduate years profoundly influenced Smith, then known as Chloethiel Woodard. Willcox’s open houses and the lively discussions they inspired shaped Smith’s student experience and inspired many of her own architectural philosophies.

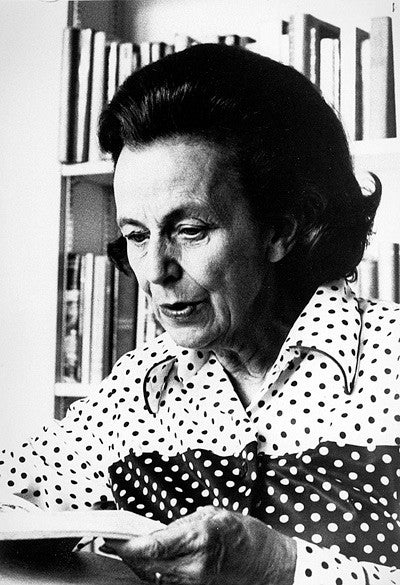

Above: Chloethiel Woodard Smith

After completing her master’s degree in architecture from Washington University in St. Louis, Smith moved to Washington, D.C., to work for the Federal Housing Authority. It was there that she first encountered the designation given by the male-dominated world of architecture to all women in her profession: “woman architect.” When asked by Old Oregon in 1979 about her determination to distance herself from the term, Smith replied “I’m an architect with a capital A. Being a woman has nothing to do with it.”

It is this strength of character and conviction that allowed Smith to become one of the most influential builders of America’s capital after World War I. A 1942-44 stint as a professor of architecture at the Universidad Mayor de San Andres in La Paz, Bolivia, lead to a 1944 Guggenheim Fellowship for Humanities for her research in South America. While Smith initially traveled to Bolivia as a result of her husband’s State Department posting, she once again proved her resilience and ability to stand apart from the crowd while there.

Smith formed Keyes, Smith & Satterlee in 1950. It was with this firm that Smith became known as a champion of the Washington Southwest Urban Renewal Area Project, for which she worked as master planner and architect. Urban renewal projects in Washington were a specialty of Smith’s, works she believed to be necessary to fostering a vibrant community in a city marked by huge wealth disparities, which often translated into discordant architectural styles.

In 1964, Smith designed Waterview, a group of townhouses on Lake Ann known for spiraling steps leading directly into the water. It was this eye for beauty that became one of her trademarks. When describing her attitude toward design in Home Builder Magazine in 1965, Smith said “Beauty doesn’t jump onto the drawing board with a sheet of working drawings, or onto the concrete truck or the mason’s trowel. Beauty comes shyly into the designer’s office.”

As time passed, Keyes, Smith & Satterlee was transformed into Chloethiel Woodard Smith & Associates. By 1967, Smith was at the helm of the largest female-run architectural firm in the United States, working as a planner and architect for an enormous number of projects, including the National Airport Metro Station, the Universalist church in Rochester, New York, and the Washington Channel Bridge. She retired in 1983.

Over the years, Smith served on the boards of the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the President’s Council on Pennsylvania Avenue, the Committee of 100 on the Federal City, and the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. It was this dedication to her craft that earned her the Centennial Award for “continuous service to the chapter, the community and the profession” from the Washington AIA in 1989.

Smith died December 30, 1992, leaving a legacy of passionate service and courageous refusal to accept any less than the full respect she deserved, despite traditional gender roles of the day. She will forever be known as the woman who built modern Washington and paved the path for women working toward the goal of becoming architects – with a capital A.