bachelor of architecture '72

‘Graphite Era’ graduate’s success a cross-pollination of specialties

As a UO student during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Stanford Hughes says he was taught during “The Graphite Era.”

Above: Stanford Hughes. All images courtesy BraytonHughes.

Computer-aided drafting and color printing would not become the norm in the architecture profession for a few more years. As a result, students in the UO Department of Architecture drew every design, idea, and diagram by hand.

Hughes, BArch ’72, got plenty of practice executing hand-drawn designs when he chose for his undergraduate thesis a study that analyzed Eugene’s 13th Avenue from Willamette Street to the UO campus. The final product, printed in 24 copies then stitched together, opened up to a 12-foot-long display that was hand-drawn and silkscreened in three colors.

“It was a provocative master plan and vision for the future, dealing with the potential of private, public, and institutional places,” says Hughes.

Hughes’ college roommate Brad Van Woert recognized Hughes’ potential early on.

“I think he was born to be an architect. You could just tell from the very beginning,” says Van Woert, who graduated with Hughes in 1972. “He has this incredible, intuitive sense to design and technology that’s both classical and creative.”

“I call him The Natural—the Roy Hobbs of architecture,” he adds, referring to the fictional baseball player portrayed by Robert Redford in the 1984 film.

That innate ability, and the portfolio he created using his talent and his education from UO, was recognized in 2015 when Hughes was one of four people in the United States inducted into the International Interior Design Association (IIDA) College of Fellows.

Hughes, a LEED-accredited professional who was elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 2004, was founding principal at the San Francisco-based design firm BraytonHughes Design Studios from 1990 until last year, when he divested ownership in the firm. He now serves as a consulting designer.

Hughes praises his UO architecture professors for bringing an array of backgrounds to their teaching.

“We had an interesting mix of east-meets-west professors,” he says. “They’re the ones who imbued this world philosophy of design and the art of architecture. It was really just a matter of connecting with some really enlightened individuals who were teaching there at the time.”

Professors from Princeton University, University of Pennsylvania, University of Texas, and other architecture schools across the country were among the career-track architecture instructors who Hughes remembers.

“They were diverse and had different philosophical approaches,” Hughes says. “That made us as students define what made sense. There was no single approach or philosophy.”

Exposure to that breadth as well as depth in studio classes helped set Hughes on the path that led to his many professional successes. San Francisco-based BraytonHughes gained an international reputation for designing hotels, executive offices, historic renovations, and residential spaces. In 1996, Interiors magazine named the firm “Designers of the Year.” Hughes was inducted into Hospitality Design magazine’s Platinum Circle in June 2015.

BraytonHughes also helped design Cavallo Point in California, the first National Park site to earn Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) gold certification.

Above: Cavallo Point Lodge, set on a former military base in Sausalito, California, was the first National Park and the first site on the National Register of Historic Places to earn LEED certification.

Hughes also has taught architecture, beginning with a third-year architectural studio at UO in 1976. He later taught at University of Pennsylvania, The California College of Arts, and Drexel University.

Hughes says his career took off after former UO Professor Thom Hacker, who was Hughes’s thesis adviser, introduced him to colleagues in Pennsylvania. “He was the one who really inspired me to go back to Philadelphia,” Hughes says. “That was the mentor who established me, really. Having that personal introduction made all the difference for me.”

It also inspired him to move to Pennsylvania, where he secured an apprenticeship with Venturi Scott Brown. His final position with Venturi was as project architect for the interior of the Knoll Inc. Showroom, a prominent furniture and textile company in New York.

“I had the reputation for expertise in interiors and interior architecture, which established my specialty as an interior architect,” Hughes says.

After seven years, Hughes moved back to California and met future firm principal Richard Brayton at Bull Field Volkman Stockwell’s San Francisco office. Both Brayton and Hughes were senior designers and became friends.

In 1981, Hughes joined the distinguished international design firm of Skidmore Owings and Merrill in San Francisco. In the ensuing years he became an associate partner and director of the Interior Design Department prior to cofounding BraytonHughes Design Studio with Brayton in 1990.

BraytonHughes’s first project was a Sheraton hotel in New Caledonia, a French territory in the south Pacific. The firm also designed corporate interiors for office buildings simultaneously. These projects dovetailed into the company’s varied practice of designing both hospitality and corporate interiors.

“We like to say that when we do houses, it informs the way we do offices. When we do offices, it informs the houses. When we do hotels, it informs the offices and houses,” Hughes says. “It’s a cross-pollination of specialties.”

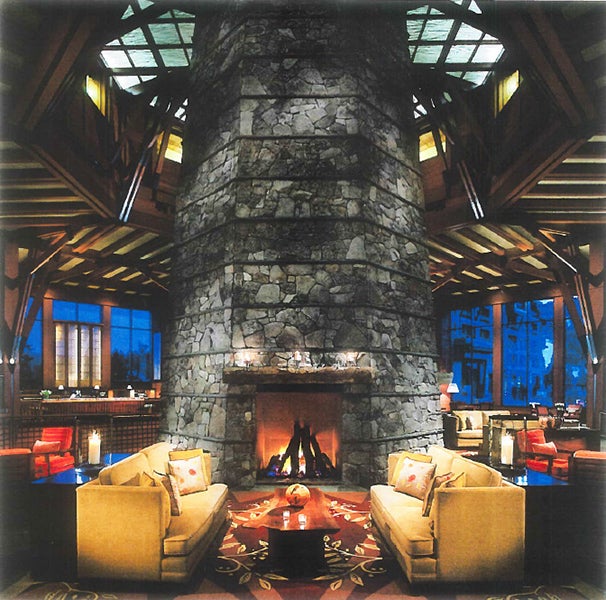

Above: The Lake Tahoe Ritz-Carlton, a BraytonHughes design.

In 1998, BraytonHughes paired with Santa Monica architecture firm Moore Ruble Yudell to win the design competition for the new U.S. Embassy in Berlin.

The project took six years to gain traction; the embassy was designed to be a showcase of American design and technology, with conference rooms and visa administrative facilities.

“That was quite a great honor and experience and it turned out quite beautifully,” Hughes says. “Collaborating with Moore Ruble Yudell was an excellent process.”

This experience led to other collaborations including the U.S. Federal Courthouse in Fresno, California.

Hughes’s favorite project with BraytonHughes is the historic renovation of Cavallo Point Lodge, a resort set on former military base Fort Baker, just north of the Golden Gate Bridge in Sausalito, California.

Half of the lodge comprised historic buildings that could not be modified, while the other half was recently constructed buildings. The firm had to find a way to design the drastically different buildings’ interiors without drawing attention to their dissimilarities. An historic architect oversaw the historic buildings to preserve their character, while a contemporary architect addressed the new buildings.

“The fact that we did interiors on both the historic and the new contemporary buildings and they all have this seamless quality was kind of a unique example of our design talent,” Hughes says.

The redesigned lodge housed residential units, a spa, restaurant, and meeting rooms.

“It’s my favorite because it touches on the historic and contemporary,” Hughes says. “It has a nice variety to it.”

The destination lodge, a member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s Historic Hotels of America program, was certified LEED gold in 2010; it’s the first National Park and the first site on the National Register of Historic Places to earn LEED certification. The lodge also received the 2015 National Geographic Legacy Award for Sense of Place.

“If you look at Stanford’s body of work, it’s not like every job looks identical to another,” says Van Woert. “He’s got a really sophisticated, eclectic style. Each design is responsive to the context of the client and the environment he’s working with. It’s really to be commended.”

Although the practice is very diverse, the unifying elements among BraytonHughes’s work, Hughes says, are their high-quality and site-specific designs that embrace each project’s “sense of place.”

“Each one is responding to the client as context, site as context, and the spirit of place,” he says. “Each one develops the uniqueness based on those elements and contexts.”

Notes Van Woert, “All his work tends to be timeless. He’s made to be what he is now today. You could tell from get-go.”

Above: This private residence in a chardonnay vineyard in Woodside, California, is another BraytonHughes design.