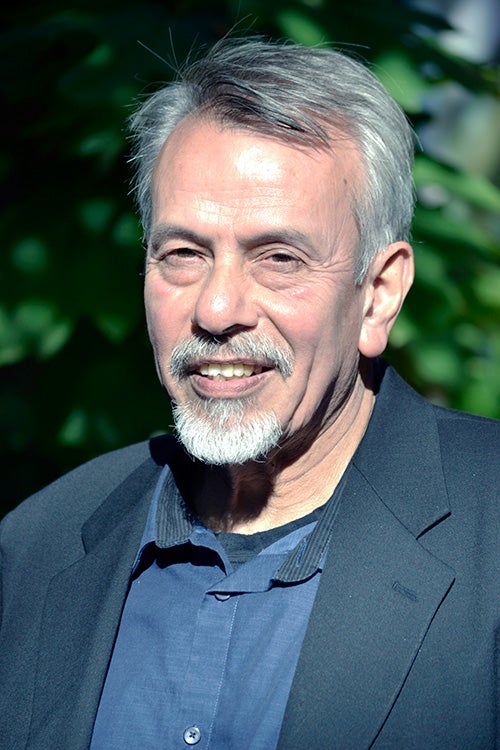

bachelor of architecture ’71,

master of architecture '86

Paz advocates for sustainability, ecological intelligence

Architect Artemio Paz Jr., AIA, has transformed much more than spaces into cultural artifacts in Oregon. While serving eight years on the Oregon State Board of Education, Paz encouraged school curricula to embrace a deeper understanding of ecological intelligence.

“Oregon’s environmental legacy and richness of the natural environment was really captivating for me,” says Paz, whose tenure on the education board included serving as chairman.

“Oregon’s environmental legacy and richness of the natural environment was really captivating for me,” says Paz, whose tenure on the education board included serving as chairman.

Paz, principal at APAZ Architect, AIA, in Springfield, Oregon, infused his knowledge of architecture and urban planning to improve environmental education, pushing for terms such as “sustainability” to become essential language in Oregon classrooms. His professional work shows an approach to sustainable design that ranges from the Torrance Performing Arts Theater in California, the Emerald Art Center in Springfield (LEED existing buildings pilot program), and the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza in Eugene, to the City of McMinnville master plan preserving Hotel Oregon and the city’s Carnegie Library.

“I’d like to think that I’m sharing my architectural background in the broader landscape,” explains Paz.

Paz has dedicated much of his public service as a voice for minority students in Oregon, after growing up with two Puerto Rican parents. He has served on numerous boards in Lane County, including the Hispanic Business Association, Springfield Arts Committee, Networking for Youth, and Eugene Schools of the Future, among others.

Q: You recently completed eight years on the Oregon State Board of Education, including serving as chair. What did you hope to achieve in your time on the board?

A: While there, I stressed the notion of an aesthetic sensibility, a form of contextualized learning, as being critical to our education innovation for young adults, as well as ecological intelligence and its importance for critical decision-making in the 21st century. We all need to be really sensitive to the natural environment. That sensitivity needs to be integrated into public education in a comprehensive knowledge base not just through vested interest groups, such as architects demonstrating design of energy-efficient buildings, but rather a more inclusive framework focused on whole systems within cultural environments that structure and create long-term sustainability and well-being.

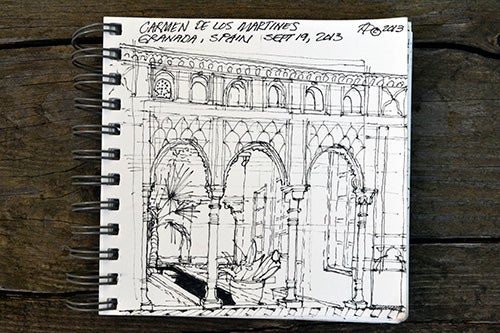

Above: In September 2013, Paz toured Europe, making sketches en route including of the Carmen De Los Martines in Granada.

Q: How did your background with architecture affect your decisions on the State Board of Education?

A: There’s quite an emphasis on STEM [science, technology, engineering and mathematics] education coming from the Department of Education at a national level. To me, it emphasizes the left brain, an engineering mentality. I agree that it’s important, but unless you put design in it, you are dealing with isolated factual information. I’m not certain of its appropriateness until we start talking about design sensibility and relationships between factual pieces. I frequently cited the importance of the arts that include architecture, visual arts, and art venues such as handcrafts that manifest creativity, innovation, and explore the magic of critical thinking, problem solving, and economics.

Q: Has your perspective on education changed since you attended the University of Oregon?

A: You’re not sure what your discipline is all about when you’re going through school. So you’re forced to focus on one particular aspect and look to faculty colleagues as partners to explore ideas. John Reynolds, Charlie Brown, John Briscoe, Pasquale Piccioni, and Thomas Hacker were those professors instrumental in helping me articulate notions beyond general ideas to creative particularization and distinct beauty. After my formal education, I realized that architecture is extremely idiosyncratic and requires learning with exquisite specificity and listening with a keen sense to client and community program nuances.

Above: Paz, Architect for Campus OSU Foundation contemporary office redesign. Photograph courtesy Artemio Paz.

Q: How did the UO help you succeed in your career?

A: I think that the U of O School of Architecture helped me understand that you need to network with creative people. Consequently, my contacts with campus faculty also included relationships off campus and in the business community. I began to understand [that] giving back to the community was extremely important and that engaging important, genuine community conversations on urban planning and building design was essential for successful public space design that democratizes urban experiences. This network process … continues in a collaborative manner today.

Q: Considering your background at the UO, how do you believe arts education is faring today in the public system?

A: Not very well! The arts are underfunded and underemphasized. My UO architectural education focused on design theory and related to renewable energy systems, building structural systems, and the contextual influence of building sites. I think the beauty of my campus experience was its focus on issues related to developing an aesthetic sensibility, notions of architectural sustainability, and architecture’s relationship to natural environments. It’s hard to measure the significance of an art education, but I think it’s so powerful and is lacking in most PK-14 public school environments. The arts and its discretionary decision-making is traditionally embedded in rich intergenerational wisdom, local knowledge, and skills that are fundamentally absent from the current educational reform nationally and correspondently absent locally. There are exceptions in Oregon’s public schools, however they are few and frequently privileged.

Above: The Santa Maria Delle Quattro Fontane in Rome captured Paz’s attention during his 2013 European tour.

Q: While you were on the State Board of Education, how did you contribute to issues that you are most passionate about?

A: Transforming STEM education by adding an “A” to make it STEAM. And the “A” is for the “Arts.” However, my passion lies in adding an “Ei” to the end of STEAM to make it STEAMEi to incorporate “Ecological intelligence.” The lowercase “i” recognizes that intelligence is something that has to be free of hubris and sensitive to a deeper intelligence of how we relate to our natural environment and cultural commons. All those people talking about STEM are missing the point if they are not looking both for an aesthetic sensibility, a cultural framework, and conditions of ecological intelligence. I shared this “Ei” view, in addition to describing Oregon’s 40-40-20 Vision and its student-required demonstration of “Essential Skills” with a delegation of Chinese [at a] Harvard University meeting in April 2013. Furthermore, I have shared this “Ei” concept in the form of an algorithm presented to a consortium of over thirty states meeting to discuss adoption strategies for the Next Generation Science Standards. Finally, I introduced to the board [that] subsequently adopted the idea that global awareness was a critical essential skill.

Q: What would you suggest students do at the UO get the most out of their time while in school?

A: Understand what is happening in the classroom but search for articulate models or case studies in the community. It’s very important to experience a contextualized design. Take the program, find out how people have understood it historically, and then move into the contemporary sense and apply it to the local community. And always have that reference to the ecological intelligence in the decision-making process, because we’re looking for resiliency and long-term well-being in the structures and spaces that we create.

Above: Paz notes the design of the Torrance Performing Arts Theater in California as one of his most notable architectural career achievements. Photograph courtesy Artemio Paz.

Q: Do you plan to continue to serve the public as you have in the past?

A: I’m presently writing short articles on the culture of informed learning linked to ecological intelligence and its relationship to American education reform. From this work my intent is to structure chapters for future books. In addition, I plan to consult and teach at schools of education while also consulting with architects and schools of architecture on related school facility design.

The emergence of severe climate change issues is changing the pedagogical, metaphorical analogs, and language of classroom critical thinking and its impact is not solely on subjects of science and math. Our notions of resiliency and forms of sustainability in all fields of study and research are rapidly changing—and it’s not primarily driven by new technology. Our concerns for clean air, clean water, biodiversity, rising sea levels, excessive CO2 in our air and oceans, the loss of sea ice and mountain glaciers, to new forms of green medicine, nutrient rich organic agriculture, and green architecture are transforming classroom and community learning environments globally.

Above: Paz, Architectural Design Consultant of the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza on 8th and Oak in Eugene. Photograph courtesy Artemio Paz.

Q: What are you most proud of professionally?

A: The design of the Torrance Performing Arts Theater in California. My role as the project designer for a 500-seat theater with an additional 100-seat black box theater incorporating a traditional Japanese garden, creating a cultural connection to the Japanese American community, was architecturally extremely rewarding. I framed the semi-public garden courtyard area on three sides with rehearsal and dance rooms studios and on the fourth side nestled it against the main theater for intermission viewing by theater patrons. The challenges included working with a community advisory committee, a constricted site with multiple existing buildings and access points, multiple program users, project approval from the city council, and final design development consultation. The spatial organization explored daylighting, passive solar heating, and diurnal cooling of the smaller studio spaces.

Other projects include the UO Chiles Center Addition, the Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza in Eugene, the PFF office building in Springfield, the H.U.D. Passive Solar Demonstration Project for the federal government, the McMinnville City Master Plan for its historic central business district, and my master’s thesis interview and guided tour with Dr. Jonas Salk while he related stories of his interactions with L. I. Kahn, the architect of Salk Institute.

Above: Paz’s sketch of a balcony in Barcelona.

I found meeting with people who had worked with Louis Kahn and my examination of his work changed the character and quality of how I view comprehensive architectural design.

Q: It’s evident that you are involved with the community beyond your architecture firm. What motivates you each morning to get up and do the things that you do?

A: I’m trying to figure out how to give back. As a young architectural student I traveled through Europe from London to Istanbul in the ‘60s. I was most enthralled with 15th century painting, sculpture, and architecture—I really wanted to be a person that lived in that century! Now I firmly believe that this is the most exciting century in human history. This century—which will be the most challenged in history to create a global insight informing the preservation of planet Earth, with a new species meritocracy, with cultural richness in language diversity, with exquisite specificity in place-making—will create and maintain innovative and healthy workplaces for families that realize local and global sustainability, good health and well being. And that is very special.