bachelor of architecture ’68

Miller an ‘intensely committed educator, administrator, scholar’

Like many California high school students interested in architecture in the early 1960s, William Miller was drawn to the University of Oregon’s undergraduate program. The Sacramento native estimates that almost half of his class was also from California. “To me, it was a fortunate choice,” he said. “It was an incredible period of change, and Oregon was an open place that embraced those changes.”

Above: William Miller, BArch ’68—shown here during graduation ceremonies at the University of Utah in 2008—teaches his studios like he was taught (at UO).

Miller went on to a forty-plus year distinguished career as an architect and educator, working in teaching and academic administration at three institutions—the University of Arizona, Kansas State University, and the University of Utah—while designing projects nationally and internationally. In 2013, the Utah chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) honored Miller with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

“Bill exemplifies the intensely committed educator, administrator, and scholar,” the award citation read, praising Miller “for his contributions to architectural education and practice. His exemplary educational and administrative achievements make him an invaluable resource to the design community through his development of strong active professional programs, and forging positive reciprocal relationships with the public, the profession, and the academy.”

A licensed architect in Arizona, Kansas, and Utah as well as an NCARB certificate holder, Miller was elected to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects in 1997. He practiced in Sacramento, California; Anacortes, Washington; San Francisco, California; Tucson, Arizona; and Manhattan, Kansas, in addition to completing numerous independent projects over the years. He has had projects published nationally and internationally, and has placed in several architectural competitions.

As an educator, Miller championed innovative architectural design studio curriculum that integrated technological concerns with social and cultural issues in rigorous studio settings. These studios often made use of community service projects, public or institutional clients, and involved cooperative team-based design work.

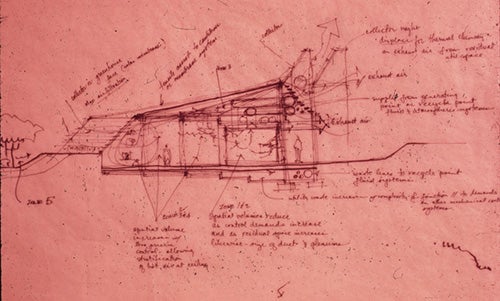

Above: A design sketch by William Miller illustrating the section for the University of Arizona Animal Resource Center Project. The design demonstrated a number of sustainable energy and design strategies for a project executed in a hot arid region.

As dean of the University of Utah College of Architecture and Planning from 1992 to 2002, Miller encouraged his students to experiment in studio, based on what he learned in Oregon’s ungraded, pass/fail classes. “You don’t learn by getting an A, but by taking risks and failing,” he says. “I haven’t seen that at other places. Architecture is cyclic process that demands inspection, critical inquiry, and appreciation of craft, among other things. The nongraded studios [at UO] allowed for a student to take an idea and explore it to its fullest potential, and if you went into a blind alley you were not punished for it (that is, get a bad grade). This culture of rewarding engagement and critical inspection informed how I taught studio and looked at curriculum as a faculty member over my forty-year career.”

UO also introduced him to some of the more influential architects practicing at the time. As a UO student, Miller fondly recalls an intense week of meetings and lectures with “young emerging (now well-known) architects” such as Michael Graves. “It adjusted my view about architecture,” Miller says. The visiting professionals “presented their work, held discussions on architecture theory, conducted studios, and critiqued each other’s work—all in public sessions,” Miller says.

“This changed my view of architecture to one that was about intellectual content and inspection, not just functional or pragmatic issues,” he says. “This was also a time when Don Lyndon and Robert Harris were heads of the department. They brought in a cadre of young, highly skilled educator-practitioners that transformed the curriculum and the content of the design studios, which also influenced my studio teaching.”

When he graduated, Miller “anticipated that I would work in a firm and after licensure seriously consider forming my own office—a normative trajectory,” he said. “But after working in the profession for a while I felt the need to go to graduate school to delve deeper into architecture and its processes. And that changed my direction because I was a teaching assistant there and enjoyed it—obviously, since I moved to teaching after that experience.” Miller received his MArch at the University of Illinois, Urbana.

During his thirteen years as an academic administrator of two programs, Miller provided leadership through developing and promoting strong professional programs and forging positive, reciprocal relationships among the public, the profession, and the academy. The architecture program at Utah, often working in concert with AIA Utah and other community and arts organizations, functioned as an intellectual as well as social force in the design community.

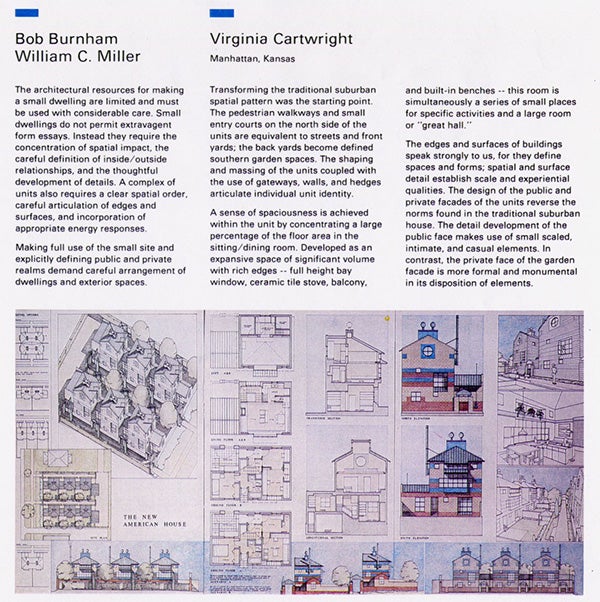

Above: From the catalogue of award winning projects for the national “New American House Competition.” This entry, for a small dwelling complex in Minneapolis, co-designed by Bill Miller, Virginia Cartwright (associate professor of architecture at UO), and Robert Burnham received an Honorable Mention Award.

Miller’s academic career was complemented by service on the boards of directors of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA) and the National Architectural Accrediting Board, in addition to numerous duties in the AIA and the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB).

In 1996, Miller was appointed to represent ACSA on the board of directors of the National Architectural Accrediting Board (NAAB) for a three-year term. During his term he helped develop the 1998 edition of the NAAB Conditions and Procedures, which brought important changes to the accreditation process. He was a team member on more than twenty-four accreditation visits, chairing sixteen.

Miller also served on the editorial board of the Journal of Architectural Education.In 2004, the ACSA awarded Miller the prestigious Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture Distinguished Professor Award for his numerous contributions to architectural education.

Miller was appointed the 2003-2004 Plym Distinguished Visiting Professor of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana and in 2007 was awarded the AIA Utah Bronze Medal Award. He was named to the AIA’s Educator Practitioner Network Advisory Committee for a four-year term in 2007.

Miller is also an internationally recognized scholar on Alvar Aalto and modern Scandinavian architecture (he is a Fellow in the American-Scandinavian Foundation). While a student at UO, a series of faculty lecture series every Friday, ten in one semester, introduced Miller to renowned Finnish modernist Alvar Aalto and other Scandinavian designers.

“In particular two faculty members had done sabbaticals in Finland and presented Aalto’s work,” Miller says of the lecture series. “In my fifth year I took an independent study course with one of them and then when I became a faculty member, Aalto and Scandinavian modernism became a focus of my scholarly activities.” Miller also had the opportunity as a student to meet Aalto, who at the time was working on the library at Mount Angel, Oregon.

As a result, much of Miller’s academic research focused on Aalto, including the definitive bibliography of Aalto scholarship, Alvar Aalto: An Annotated Bibliography.

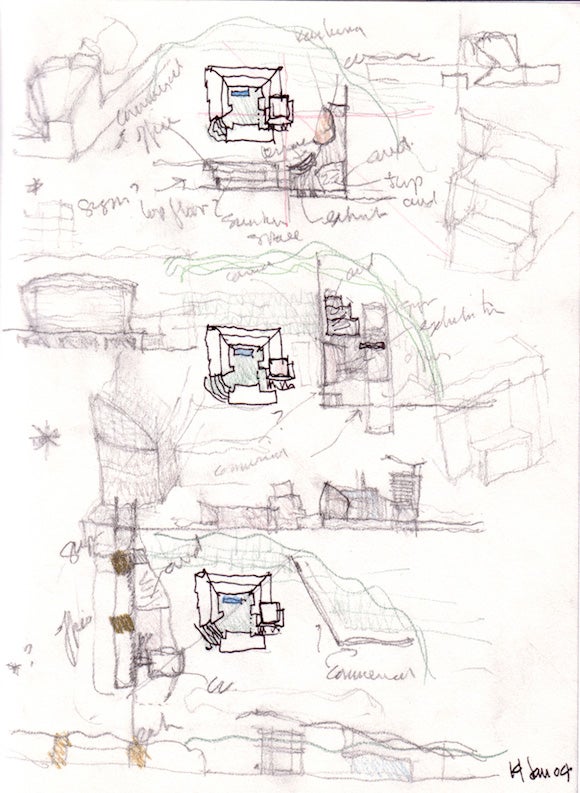

Above: Studies in a sketchbook, “(re)confronting alvar aalto: a theoretical exploration,” by William Miller. Miller is an internationally recognized scholar on Aalto and modern Scandinavian architecture, and is a Fellow in the American-Scandinavian Foundation.

Miller has also written four monographs on Finnish architecture, two dozen entries on Scandinavian architecture for six international encyclopedias, more than twenty articles in internationally and nationally published books and journals, and reviewed twenty-seven books on Scandinavian architecture for scholarly and professional publications.

Recognizing his expertise, the Smithsonian Institution invited Miller to be a study tour lecturer on their 1989 Baltic Passage educational cruise. He gave six lectures on Scandinavian and Soviet art, architecture, and design.

In addition to authoring and coediting several books, Miller’s writings have appeared in the Encyclopedia of 20th-Century Architecture, The Encyclopedia of Contemporary Scandinavian Culture, International Dictionary of Garden History and Landscape Architecture, International Dictionary of Interior Architecture, International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture, The Encyclopedia of Architecture, The AIA Gold Medal, ptah, The Senses & Society, Polis, Forum Journal, The Journal of Architectural Education, The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Progressive Architecture, Architecture & Urbanism, The Architectural Association Quarterly, and Faith & Form among other publications. He has presented numerous scholarly papers, and served on many design award juries.

From working in firms to teaching and other public service, Miller can claim an extensive career range, yet one that kept a continual focus on architecture education.

“I feel very, very lucky to have had the career in education that I have had. Using the academic model of teaching-scholarship-service, I feel fortunate to have been a well-respected teacher who has been recognized for my teaching manner and pedagogy, and is remembered by his students,” he says. “And of course my scholarship has provided much pleasure over the years, and resulted in a number of publications, presentations, and lectures, along with a lot of trips to the Nordic region.”

Miller retired from the University of Utah in 2011 to become caretaker for his wife Beverly (BS ’68), who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2010.