He tweets in French, English, and Farsi. He’ll set up an empty chair in front of his own chair on a busy sidewalk just to see who stops by, documenting the results in photographs. His portfolio includes photographs of shopkeepers holding portraits of dead relatives; photo assemblages “created to raise suspicion”’; photographs gathered from dozens of artists and sold to benefit children with cancer, children in poverty, children in need of human rights protection.

These are just some of the projects that artist, independent curator, and now UO graduate teaching fellow Farhad Bahram has taken on since 2005, when he began freelancing as a photojournalist in his native Tehran, Iran.

Above: Farhad Bahram displays prints from his series "Live by Death” that he shot in 2012 in Kashan, Iran, of shopkeepers holding portraits of dead relatives. Photograph by Cody Rappaport.

“In Iran there is intense surveillance over all types of communication, from routine social interaction to the virtual and contextual communication inside the Internet and media,” Bahram says. “As a photojournalist, I mostly worked on photo reportages about the difficulties of social life in Iran, for example children working underage because of poverty, or about children’s violated rights.”

After years of struggling with governmental censorship, Bahram moved to the United States in 2011 to attend the San Francisco Art Institute. A year later, he decided UO’s focus on interdisciplinary studies was a better fit for his artistic and sociological intentions, so he applied for and was accepted into the UO Department of Art, where he’s a MFA candidate in photography.

Bahram sees his work as a “fusion of art and social science. Before I started my education in the U.S., I hadn’t heard about a field of study called ‘social practices.’ This talks about how artists can use the potential of social and political theories to broaden the range of influence on different audiences and the context of art experience.”

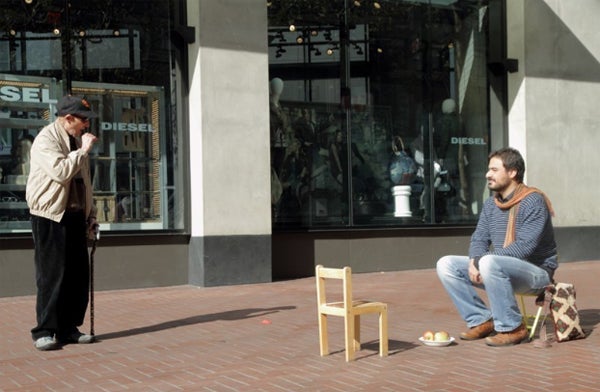

Above: An example of a collaborative, audience-dependent project was “Alternative Context,” when Bahram set up an empty chair in front of his own chair on a San Francisco sidewalk and waited to see what connections might be made. Photograph by Elizabeth Ajtay.

While still in Iran, his practice began “leaning toward the intersection of art and human sciences.” By moving to Oregon, he says, “I was looking for an opportunity to experience those other fields beside my art practice. Here there is a good parity in the MFA program between theory and studio practice, which helps me to strengthen the form and concept of my work.”

One such work is “Dialography,” a project he initiated in 2013 “seeking a collaborative dialogue on authority.” The project began with one photograph by Bahram, passed on to a second artist who was asked take another photo and put it on any side of the first image before passing it on to a third, a twelfth, a sixteenth photographer, and so on.

“It is important for me to see how different artists and even non-artists generate this sense of authority by creating something then handing over possession—and also their authority—in order to create a 'meta-lingual' interaction with others through a collaborative art object,” Bahram says. “It is an open-ended collage that they don't own solely.”

Collaboration is key to much of Bahram’s work. In 2009 he founded Global Mission of Art (GMOA), a multicultural curatorial platform involving dozens of artists from various countries.

“Because of the difficulties in working collaboratively with artists inside Iran,” he says, “I decided to start a project with artists outside of the country.” The group collaborates online to develop, curate, and present an exhibition in a different part of the world every year. GMOA has performed and presented three main projects — in Tehran in July 2010, San Francisco in April 2011, and Paris in November 2012.

Above: Farhad Bahram appeared on a Voice of America interview broadcast in December 2012.

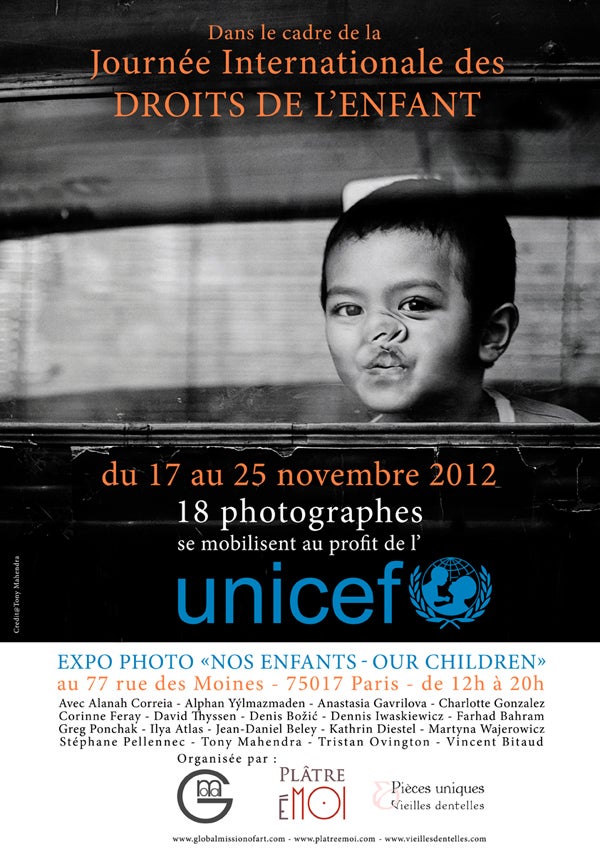

From art creation to art support, Bahram, through GMOA, has organized exhibitions and book publishing efforts, and initiated conventions and workshops globally. “Most importantly, as part of each project, I decided to allocate all the funds raised through these events to nonprofit organizations and humanitarian movements,” he says, “such as the society for supporting children suffering from cancer (Mahak), UNICEF, and now in my fourth project I am working with the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights.”

The idea for GMOA was born in Bahram’s “growing up under Iran’s stringent regulatory control. As a citizen of the Middle East, I could observe the effects of governmental mistrust of traditions,” he says. “I developed a great desire to practice ways to deconstruct what I call the ‘despotism of communication.’ This happens through the language of interaction—usually via the medium of photography. I am working on social and political aspects of art practice, mostly on broadening the range of influence on different audiences in different social contexts. ‘Collaboration’ and ‘intervention’ are two common themes in my works.”

One of his collaborative, audience-dependent projects was “Alternative Context,”, where Bahram set up an empty chair in front of his own on a Market Street sidewalk in San Francisco and waited to see what connections were made. The project supplemented another work, “Reciprocality”, where he asked people on the street to photograph him photographing them. “Through this mutual communication, I created a perpetual dialogue both with the location and the people. All of the participants could be artist and audience at the same time.”

The artist-audience interaction is a key element of his process and results. “I tend to invite my audience into the process of making art with myself instead of presenting a completed artwork to them,” he notes. “The process becomes more important for me than the art object. In these kinds of projects, the artist is degraded from his ‘glorious’ position and stands beside his audience. This interactive cycle of communication is one of the main differences between social art practice and classic studio practice.”

Bahram’s work has been exhibited and presented in Tehran, San Francisco, Beijing, Shanghai, Sydney, and Oakland. Most recently, his project “Teleography” was included in a group show of UO MFA candidates at the White Box Gallery in Portland April 28-May 4. He was interviewed on Voice of America in December 2012. He was awarded a student scholarship in 2011 by the Society for Photographic Education (SPE) and the Jan Zach Memorial Award from the UO in 2012.

Bahram’s work can be seen on his website, and he can be followed on Twitter, where he’s been known to quote Oscar Wilde, Edgar Degas, Marcel Duchamp, Kurt Vonnegut, Claude Debussy, and many other artists.

Above: “Nos Enfants—Our Children,” the 2012 Global Mission of Art (GMOA) project organized by Bahram and Georges Hattab, raised funds for UNICEF France from the sale of the artists’ work.

Story by Marti Gerdes