Stephen Wright, MS '81 Public Affairs, never expected while a graduate student in the School for Community Service and Public Affairs (later PPPM) that he would become CEO of a $3 billion annual revenue organization.

“Going to UO changed the arc of my life in really powerful and beneficial ways,” says Wright, who retired as administrator of the Bonneville Power Administration in January 2013 after beginning in an entry-level position and working his way up to lead the 3,000-employee federal agency.

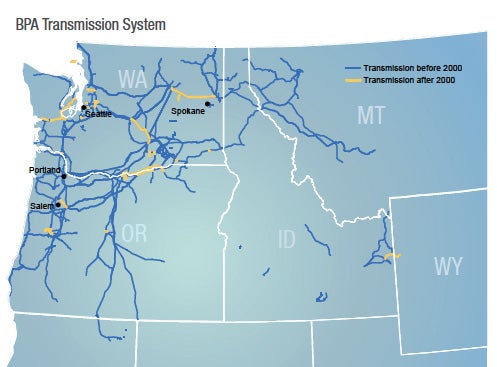

The BPA supplies 75 percent of the high-voltage transmission in the Pacific Northwest and operates the largest fish and wildlife restoration program in the world, in addition to its power-marketing role. Because it produces hydropower from the Columbia River, the agency often finds itself involved in critical issues regarding fisheries, American Indian tribes, and agriculture – often simultaneously. Wright was responsible for the agency’s decision-making in all areas.

The BPA supplies 75 percent of the high-voltage transmission in the Pacific Northwest and operates the largest fish and wildlife restoration program in the world, in addition to its power-marketing role. Because it produces hydropower from the Columbia River, the agency often finds itself involved in critical issues regarding fisheries, American Indian tribes, and agriculture – often simultaneously. Wright was responsible for the agency’s decision-making in all areas.

Wright served as BPA administrator through three presidential administrations, initially as acting administrator during the Clinton Administration. The George W. Bush Administration appointed him permanent administrator, a position he was asked by the Obama Administration to continue.

“Steve Wright … is doing important work in accelerating the accomplishment of energy efficiency and looking for ways to pair hydropower with expanded renewable energy generation,” said Steven Chu, Secretary of Energy in the first Obama Administration, when announcing the renewal of Wright’s appointment as BPA administrator in 2009. “He has my full confidence.”

A Register-Guard editorial February 5, 2013, noted that Wright’s tenure at BPA was the second-longest in the agency’s history, “which gave him time to accumulate credibility and clout. … A number of thorny problems were resolved during Wright’s tenure – the BPA and its customers reached a 20-year agreement on how power supplies would be shared, publicly owned and investor-owned utilities ended a long-running dispute over how their residential customers would benefit from low-cost hydropower, and Indian tribes dropped lawsuits over endangered salmon in exchange for increased spending on fish recovery programs,” the editors said.

A Register-Guard editorial February 5, 2013, noted that Wright’s tenure at BPA was the second-longest in the agency’s history, “which gave him time to accumulate credibility and clout. … A number of thorny problems were resolved during Wright’s tenure – the BPA and its customers reached a 20-year agreement on how power supplies would be shared, publicly owned and investor-owned utilities ended a long-running dispute over how their residential customers would benefit from low-cost hydropower, and Indian tribes dropped lawsuits over endangered salmon in exchange for increased spending on fish recovery programs,” the editors said.

For his part, Wright says, “If I had to pick out one event that made the most positive impact on my life, it would be the decision to go to UO for graduate school, where I learned skills that I did not have before, particularly how to critically analyze problems. The UO opened up career doors for me, along with how I think about challenges, whether inside or outside of work – the probing, looking for more possible solutions, trying to find good answers.”

Wright credits two UO professors in the Department of Planning, Public Policy and Management in particular for helping shape his direction. Associate Professor Carl Hosticka “was committed to public service and drove home the idea that not everyone is motivated by money, that you can be very successful creating a powerful workforce when employees understand we are doing meaningful and important work for the public.”

Wright worked even more closely with Associate Professor Ed Weeks, “who was very sophisticated with respect to his critical analysis skills. It was intimidating at first; I didn’t know how to think that way. He taught me how.”

Wright worked even more closely with Associate Professor Ed Weeks, “who was very sophisticated with respect to his critical analysis skills. It was intimidating at first; I didn’t know how to think that way. He taught me how.”

Wright met Weeks soon after arriving on campus facing an immediate $750 tuition bill but with just $700 in his pocket. His adviser steered him to Weeks, who needed a graduate teaching fellow with writing skills, and Wright had a journalism degree from Central Michigan University. “Ed turned out to be an incredible mentor. I worked for him next year as a GTF, which paid my tuition – hallelujah – but more importantly gave me the opportunity to work with Ed.”

Along with lessons from Weeks, Hosticka, and other professors and classes, Wright says UO gave him the knowledge “that I could accomplish more things than I had previously realized.”

Wright also says that “some of the best friendships of my life were initiated during my time at the UO and continue to flourish today. Maybe it was common interest, or maybe it was the shared feeling of trial by fire. Those friendships have greatly enhanced my satisfaction with life.”

Asked what inspired him to stay at BPA for 32 years, Wright doesn’t hesitate.

“First I loved the work. Bonneville was a great place for me – it’s an interesting mix of private and public so you operate in competitive markets, yet its fundamental mission is public service, not profit,” he says. “That mission was right up my alley. I love problem-solving and policy analysis, and I love working with people, the relationship piece. To be asked to lead the agency was a huge honor.

“First I loved the work. Bonneville was a great place for me – it’s an interesting mix of private and public so you operate in competitive markets, yet its fundamental mission is public service, not profit,” he says. “That mission was right up my alley. I love problem-solving and policy analysis, and I love working with people, the relationship piece. To be asked to lead the agency was a huge honor.

“Second, I am a firm believer that bipartisanship is not dead,” he adds. “Despite the dysfunction we see, there are examples where bipartisanship is still alive and well, and I’m proud to be a part of that. Finding ways to make government work, to move forward in a bipartisan way, was one of the great challenges and one of the great rewards” of his work at BPA.

Asked what he was most proud of professionally, Wright pauses for some time before answering, noting the challenge of “taking a 32-year career and boiling it down to one thing. I think probably it’s making government work effectively for people. I was hired on the day Ronald Reagan was inaugurated. He said that day that ‘Government is the problem and not the solution.’ I have great respect for President Reagan but I disagree with him on that point. Government may not always be the solution, but government can do tremendous things to improve the quality of life for people. I had a chance to live that for the past 30 years.”

One of his goals, he says, “was to have BPA respected as an institution that is there to serve people. (The agency has) three key values: trustworthy stewardship, collaborative relationships, and operational excellence. Government can operate its functions as well or better than the private sector; it just has to be committed to that. If you start from those key values, the things that got done on my watch – agreements on salmon, energy efficiency, developing contracts based on cost-based rates – they flow from the values.”

As for his future, Wright notes that “I’ve retired from federal service but haven’t really retired. I’ve got a good 10 years left of working and I will do something. I’m exploring my options right now. The one with the least income potential but the most fun for me is to write a book about how to lead in the public sector effectively, making government work, finding bipartisan solutions.”

And that’s something he’s very qualified to write about.

Story by Marti Gerdes