For relaxation, Sonia Dhillon Marty looks at architecture books. That’s how she encountered architect Erin Moore, assistant professor in the Department of Architecture at UO, who had a project showcased in a book Dhillon Marty was reading, Tiny Houses. The way the little building fit into its natural surroundings piqued Dhillon Marty’s interest. “So I Googled ‘Erin Moore’ and found her— except she was in Rome” directing the UO summer architecture program. Dhillon Marty eventually made contact, “and now Erin is a very integral part of what I do.”

Among the things Dhillon Marty does is facilitate creation of “art, design, eco-economics and socio-environmental issues” by hosting gatherings of creative thinkers from around the world, “everyone from a biologist to a dancer to an artist,” she says. Her latest invitational collaboration, with help from Moore, took place in October in Japan.

Above: From left, Ben Prager, Anthony (last name unknown), Shingi Tarirah, Donnie Brosh, and Yohei Nishida puzzle through a concern during the design charrette at the University of Tokyo. Prager was the only UO architecture graduate student at the event.

Called “Dhillon Marty Foundation Community Week,” the annual weeklong symposium connects global creative thinkers to local social and environmental concerns—in Japan, that meant focusing on how to rebuild after the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The symposium included a two-day design competition geared to create a dialogue between the visiting scholars and designers with local community members. “Collaboration … touches many people,” Dhillon Marty says, “and the energy of many creates a message much stronger than one person delivering it alone.“

For architecture graduate student Ben Prager, that “energy of many” during Community Week 2013 “transformed me. For a little over a week in Tokyo, Japan, there was a confluence of ‘awesome’ on many different scales.”

In particular, he recalls, there was “a magical moment in which (associate professor, University of Tokyo) Jun Sato, a world-class structural engineer, helped our team … take an idea we were struggling with and use a hand calculator and an elegant line to resolve our question. That moment, sitting at a desk with someone who has control over physics and structure in a way that Pele had control over a ball or Pavarotti over his voice, that moment was surreal, truly. It's magical. Architecture and design are exactly that, this transformation of something sort of foggy and aloof that might be a kernel or grain of a notion that turns into a sketch that turns into a real life thing. It's almost childlike how giddy that moment made me feel and I wish that moment upon every student.”

Instances like Prager describes are why Moore collaborates with Dhillon Marty. Moore has worked with the Dhillon Marty Foundation on two international competitions so far—at Stanford in fall 2012, and this fall at the Kengo Kuma Design Labs at the University of Tokyo, where Community Week 2013 was headquartered.

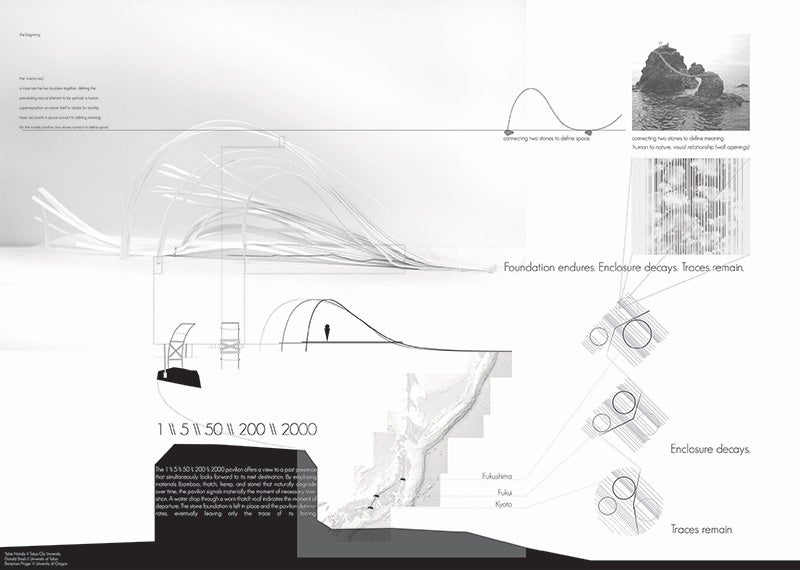

The theme of Community Week in Tokyo was “Material Equilibrium,” which centered around the rebuilding effort following the 2011 Japanese earthquake and tsunami and the 62nd rebuilding year of the Ise Shrines. The competition element of the symposium was to create a mobile pavilion for artists to work and live in. The research element included visiting the ongoing work at the Ise Shrines, which are entirely rebuilt every twenty years.

“The rebuilding of the Ise Shrines … was ripe material for considering ecological and architectural models of ‘dynamic equilibrium’ where sustainability is as much about change and perpetuation as it is about permanence,” Moore says. “The [competition] theme … spurred much thinking about different models in architecture for resilience and sustainability, especially in terms of regional ecology and building materials.”

Above: Members of the team led by Erin Moore huddle over computers in the Kengo Kuma Design Labs during Community Week 2013’s design competition.

For her part, Dhillon Marty notes that, ”In Japan, there is a tradition of moving shrines—even Ise Shrine was traveling for many years before it was located at its present location. For me the idea of mobile pavilions was, from my objective, to revive rural Japan as Japan is facing a great issue on how to keep younger people working the farms, and how to help the farmers make a living of the farm. As I am advising the Japanese Agriculture Ministry on rural development, I am dealing with this issue closely.”

Moore was one of eight architects invited by Dhillon Marty to lead teams of international scholars through the competition. Moore’s team included students from Australia, Greece, and South Korea. (Prager, the sole UO architecture student in the group, was assigned to a team with students from Mexico, the U.S., and Japan.) Team members represented “the broadest geographical range possible,” Moore says, in total hailing from sixteen countries.

The concept for the proposal by Moore’s team can be traced back to a 2011 UO class project when her students were asked by the Roundhouse Foundation in Sisters, Oregon, to design mobile live-work studios. “The book that came out of that project helped to inspire the way the [Community Week 2013] competition was framed.”

Moore’s team began its research by reading Japanese poet Kamo no Chômei “who wrote in the 12th century about the terrible disasters he experienced—earthquakes and fires that burned up huge numbers of people and homes,” Moore says.

Anne Rose Kitagawa, head curator and director of Asian Art at the UO Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, and a participant in the symposium, had suggested Chômei as a starting point. “He compared the terrible transience of his friends and their houses with the beautiful transience of dew drops and flowers,” Moore says. “Our team was thinking about this as we visited the epicenter of the March 2011 megaquake and tsunami, an example of terrible devastation, and as we visited the Ise Jingu shrines.”

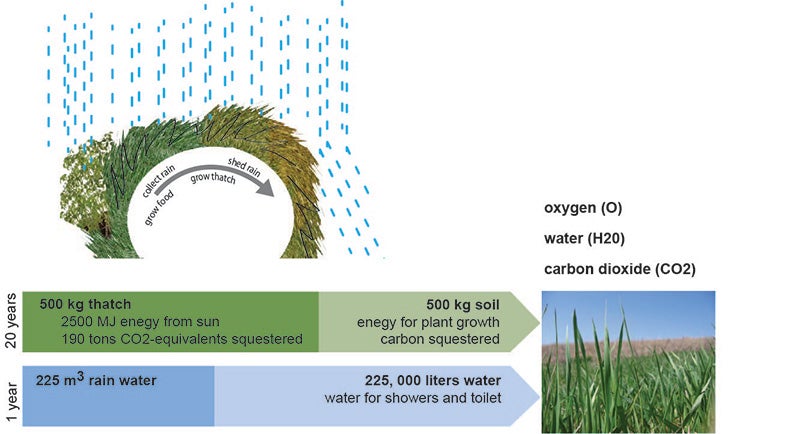

Above: Moore’s team developed various information boards including this rendering of their proposal.

The context of rebuilding and renewal at the shrines was “a beautiful example of embracing the inherent transience of traditional building materials,” Moore says. “In that context, it was easy to be inspired to design small, to design mobile, and to design for the materials of the structure to grow and to die.”

The competition guidelines gave leeway to the specific function of the pavilions, Moore notes. As in the Sisters, Oregon, project, the design by Moore’s team in Japan “proposed that the pavilion be a kind of trailer house in which artists could live and work as they move from community to community. The requirement that the pavilions would be mobile was very formative. We chose to presume that ours would be compact and moveable.”

For its efforts, Moore’s team received the “Material Equilibrium” award for a pavilion that used a spiral of thatch to capture and shed water, to sequester carbon in the plant material, and to offer a medium for the growth of more plant material.

The design fit well with Dhillon Marty’s philosophy. “Part of what I am looking for in my work with the Dhillon Marty Foundation is finding ways to reconnect people with both fundamental morality and with beauty,” she says in an interview Moore conducted with her for the online September 2013 Metropolis. “The objective of the foundation is to re-root today’s globalized society. Using art and design to communicate messages makes it possible to transcend religious or national barriers. Design is a very old and inclusive form of communication.“

One message communicated to Prager was how time and economics factor into design. “We were standing in the forest during a typhoon,” he says, as a guide explained how the trees would be harvested in 200 years—not the 50- or 80-year cycle typical in the United States. “It's a time scale on which we simply don't operate within the U.S., in particular in publicly traded companies that have quarterly earnings reports,” says Prager, who has worked on Wall Street and has an MBA. “After my visit to the Ise Shrine and seeing how a systemically different understanding of time can directly translate into an alternative valuation system for a company, I haven't been able to reconcile how the benefits of each scale (quarterly and bicentennial) can merge. It's turning into quite the ethical and intellectual quandary for my MBA brain that I'm attempting to address in my [architecture master’s] thesis.”

Along with that ongoing quandary, Prager’s takeaway from his week in Tokyo was a reminder of “what it's like to lose myself in the childlike whimsy of imagination and connect it to an adult intellectual interest transformed into a career path.”

As for Moore’s role in the competition, Prager says she was “inspirational in her approach to the mobile pavilion design, both in her attention to design quality and innovative and responsible material choice. She's kind of a gift to the architecture student body.”

More about the Dhillon Marty Foundation and additional photos of the charettes and awards from Community Weeks in Japan and at Stanford (Champ de Portola) can be found here.

Moore’s complete interview of Dhillon Marty in Metropolis Magazine is available here.

Above: A diagram by Moore’s team shows how oxygen, water, and carbon interact in their proposed project.

Above: Prager’s team produced this board illustrating the team’s proposal for a pavilion.