The scene is a lazy day on a white-hot beach. Scattered across the sand are sunbathers reading magazines, scrolling through phones, and chatting with fellow beachgoers while the sounds of seagulls and ice cream trucks ride the breeze.

The beachgoers also occasionally break out into opera, singing about vacation plans and the environmental crisis, as viewers watch from the balcony of a warehouse where the whole scene unfolds, inside and artificially lit. This art installation, “Sun and Sea (Marina),” is the award-winning entry for the Lithuania Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Art Biennale.

“The piece has to do with ecological issues and the Anthropocene,” Vaiva Grainytė, one of the creators of the piece, told Artnet. “But I didn’t want to be didactic because it’s such a big topic and it was important to find a subtle, romantic language.”

“Sun and Sea (Marina)” will be one of the examples Assistant Professor Emily Eliza Scott, who has a joint appointment in Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Environmental Studies program, uses in her new course this fall—Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change (listed in the UO catalog as ARH 399, Sp St Climate Change).

The course explores contemporary art, arts activism, and visual culture in relation to climate change, as well as the representational challenges climate change poses. The course has no-prerequisites and is open to all students.

“It’s not just a scientific problem, or an economic problem, but it’s an issue that touches on everything—the social, ethical, and representational,” said Scott, who joined the College of Design in 2018. “How do you picture climate change? In many ways it escapes or resists straightforward representation.”

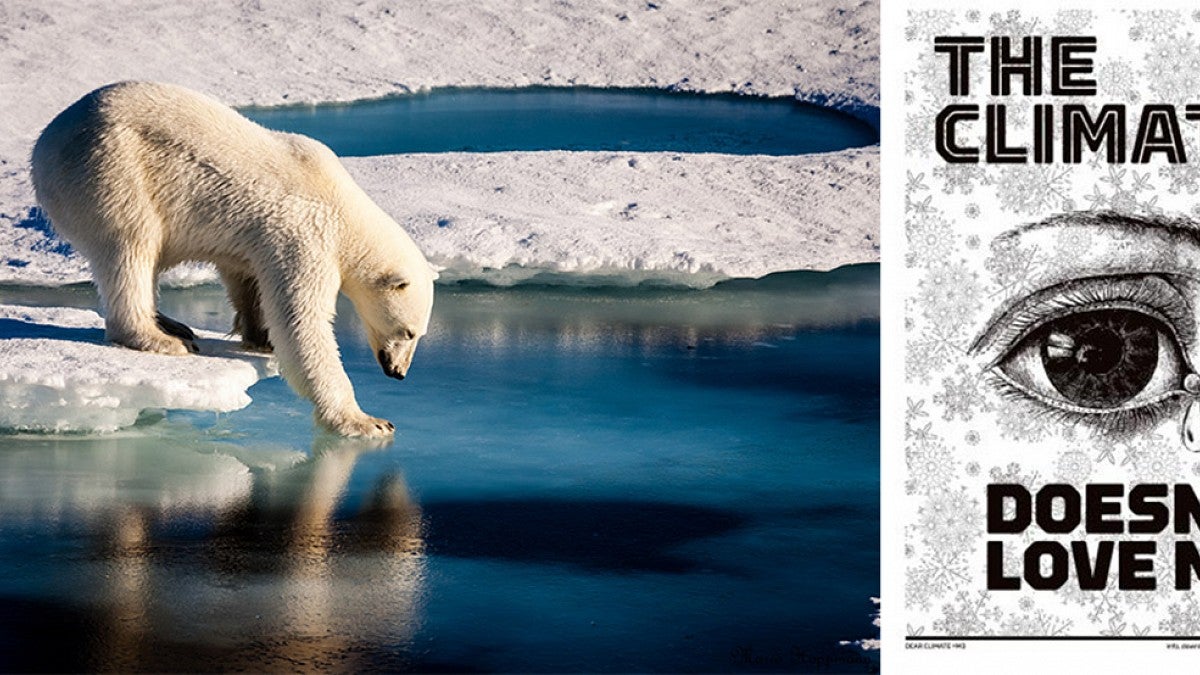

The ubiquitous images that have been used to depict climate change—of lonely polar bears on dwindling ice or cities flooded with water—don’t capture the whole story, she explained. Additionally, she noted that even climate change denialism has its own visual culture and rhetoric.

Scott has published and taught about climate change before, including two courses as a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

This past summer, she was also one of three invited artist-theorists to run a weeklong workshop on climate change and cultural production at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami. One focus of her workshop was climate change-prompted gentrification. For example, as the rich increasingly sell off waterfront property in search of higher ground, they are displacing black and brown communities that have historically lived inland (many of whom are actively organizing to resist such trends).

Along with University of California Santa Cruz Professor T.J. Demos and artist-activist-writer Subhankar Banerjee, Scott is also currently co-editing the Routledge Companion to Contemporary Art, Visual Culture, and Climate Change (expected in 2020), which aims to be a primary textbook in the field.

“There has been undeniable and ample evidence of human-caused global warming for decades, yet the crisis has a certain complexity and sometimes invisibility upon which climate change denialists—largely sponsored by the fossil fuel industry itself—have capitalized,” Scott said.

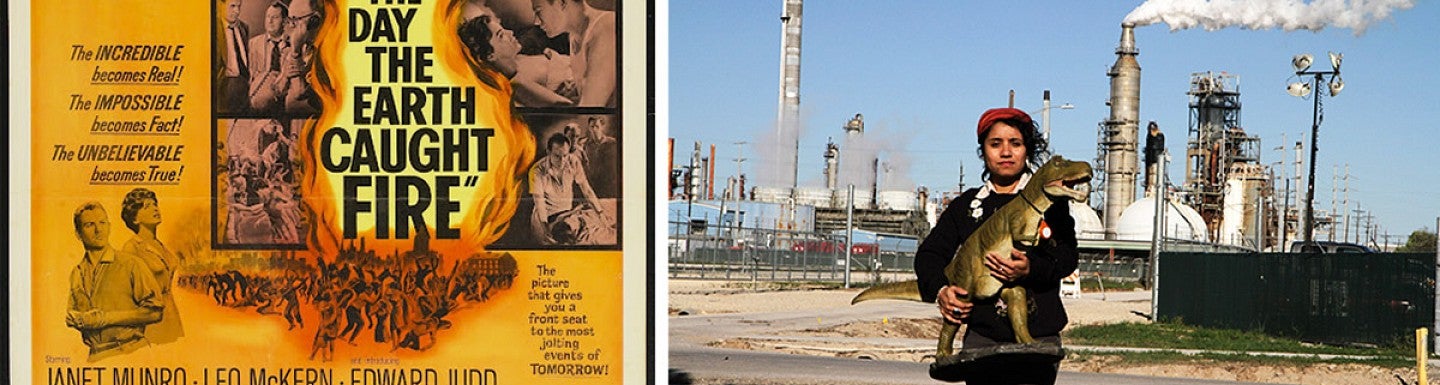

The first part of the course will focus on visual culture, exploring imagery from science, activism, and mass media, including films from both the documentary genre and that now dubbed cli-fi (climate fiction).

The second half will focus on specific artworks and initiatives such as “Sun and Sea (Marina)”; “Ice Watch” by Danish artist Olafur Eliasson, who transports centuries-old icebergs from Greenland to city squares around the globe—most famously during the United Nations COP 21 climate meetings in Paris; and more activist projects such as The Natural History Museum, which, as Scott says, “takes aim at the fossil fuel sector by way of toxic tours as well as interventionist tactics within (real) museums of science and natural history.”

This past May, Scott invited the Natural History Museum founders Beka Economopoulos and Jason Jones to the UO to speak on how the infrastructural power of museums can be leveraged to protect natural and cultural heritage, and to amplify indigenous perspectives.

Scott encourages students from across the university to register; a background in art history is not required.