Hello Kitty is not, in fact, a kitty.

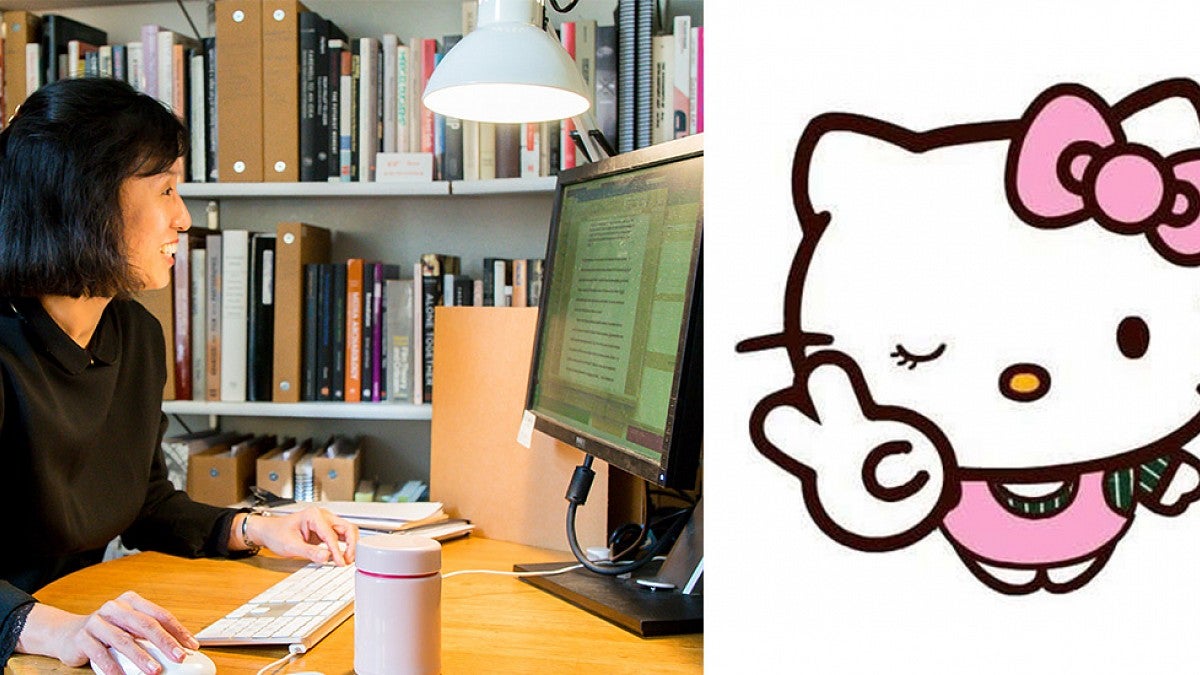

Sanrio’s announcement in 2014 about its beloved feline character with a bow shocked fans worldwide; it was also an entry point for Associate Professor Joyce Cheng—in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture—to research and write “The Rhetoric of Hello Kitty,” recently published by the University of Chicago Press journal RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics.

“In August 2014, months before the opening of the retrospective exhibition Hello! Exploring the Supercute World of Hello Kitty at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in Los Angeles, the public learned to its consternation that the popular character produced in 1974 by the Japanese gifts company Sanrio was, in fact, ‘not a cat,’” wrote Cheng in the article.

Cheng goes on to explain that Sanrio corrected the curator Christine Yano, who had indentified Hello Kitty as a cat, and informed her that she was, in fact, a little girl who lives in London.

Controversy ensued, Cheng pointed out, with defiant comments such as a tweet cited by the Los Angeles Times: “Hello Kitty is a cat. She has whiskers and a cat nose. Girls don’t look like that. Stop this nonsense.”

“In a way that controversy came about because Hello Kitty entered into something like an official cultural institution. The media frenzy was quite absurd. People were upset; people expressed disbelief; people jokingly questioned their whole universe—if Snoopy is also not a dog and if Micky Mouse is also not a mouse, where does that leave us?” Cheng said in an interview with the College of Design.

“I came to the conclusion that the meaning [of Hello Kitty] is not transparent, which is what excites me,” Cheng added. “What was fascinating was that there was an identity for Hello Kitty that the users couldn’t actually accept. As a scholar of Surrealism, I was struck by this. It’s exactly the kind of irrational phenomena in urban culture that used to fascinate the surrealist poets and artists in the interwar period.”

As an art historian by training, Cheng believes that the methods of visual culture and cultural anthropology can help analyze what she calls the “rhetoric” of Hello Kitty. “Anthropologists are familiar with this phenomenon: the official and vernacular interpretations of a cultural object don’t add up, but this doesn’t have to stop us,” she said. “The French literary and cultural critic Roland Barthes has shown that you can break down the message, or ‘rhetoric,’ of an advertising image without concerns with authorship. That’s what I tried to do with the image of Hello Kitty.”

Taking an inter-textual approach in her article, Cheng examines Hello Kitty’s origins in Lewis Carroll’s Alice stories and explores its connection to the maneki neko (the beckoning cat commonly found in restaurants), the mizuhiki (traditional Japanese gift-marker), and Japanese and European folklore related to the gift.

The beginning of the article is available to read at University of Chicago Press (full article available through membership or purchase).