In fall 2023, students in art history and related disciplines were given the opportunity to take associate art history professor Joyce Cheng’s course, “Art, Madness and Disability.” The class, designed for art history students with an interest in the medical humanities, examines the historical intersection between art, madness, and mental and physical disability. Throughout the term, students were able to explore topics such as premodern representations of anomalous anatomies and conditions, the modern medicalization of madness, the social exclusion of the mentally disabled, and more.

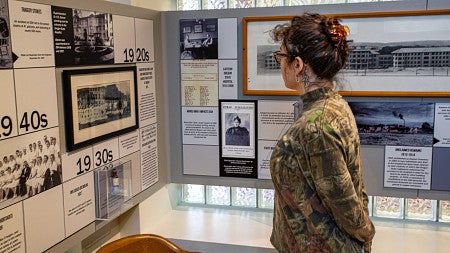

To end the fall term, Professor Cheng and a group of her students finished the class with a trip to the Oregon State Hospital (OSH) Museum of Mental Health in Salem, Oregon. The museum took students on a journey through time, investigating what life might have been like for the patients of OSH through innovations and changes in medication, treatment, awareness, and education. While there, students were able to learn how the physical and mental environmental situation surrounding patients was intentionally crafted through an array of architectural decisions and therapy styles to improve care outcomes on both a day-to-day and a long-term basis.

At the beginning of the tour, OSH Board of Directors President and tour guide Dennie Brooks set the tone by saying, “You must go into [exploring the topic of mental health] very intentionally, and look at things with an open mind, knowing that things are not this-or-that… When we go in thinking everything has to be ‘this way or that way,’ we get ourselves into a heap of trouble.”

Students were first given an overview of the OSH’s history, as well as the history of changes in medications, treatments, and even what was considered a mental illness. For example, some early indicators of mental illness outside of the obvious signs we see today were alcoholism, being married too often, and an inability to speak correctly. Unfortunately, many people were misdiagnosed. Worse yet, some of these “symptoms” were used in ways that were discriminatory and dehumanizing. Students were able to investigate the prejudices and biases that faced many of the patients in years past. Some were physically disabled, some were people of color in times of extreme racial tensions, some were extremely poor, some held beliefs in different faiths, some had personal vices, and some spoke little to no English.

Behavioral Health Clinician and OSH Board member Cynthia Prater, PsyD, spoke to the group about the OSH’s treatment of Native Americans. She is a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and has worked to concentrate on blending Western medicine, psychiatric intervention methods, and traditional tribal healing practices. Prater’s dissertation, “Listening to the Stories of American Indians at Oregon State Hospital,” as well as her own personal background gives her a unique understanding of the topic.

Prater’s conversations gave students insight into the trials and tribulations that many Native Americans and Inuit peoples faced through being institutionalized, as well as how different forms of treatments and therapy can positively affect these patients who require mental healthcare services. The group learned that many of these patients were institutionalized simply for not speaking English as well as the Americans who had settled in Oregon, or even for traditional substance uses. Inuit people were even sent to OSH from Alaska when they could not “appropriately” respond or react when questions. At these hospitals, these Native populations often faced racism, loneliness, and meals unsuited for their beliefs.

Many of these problems associated with mental institutions were addressed in Ken Kesey’s novel and Miloš Forman’s film, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Students were given behind-the-scenes information and insight into the real-life setting. Tour guide Dennie Brooks, who also worked as a location coordinator for the film, is the daughter of Superintendent Dean Brooks, who oversaw OSH at the time of filming. Though a controversial decision, Superintendent Brooks allowed filming in the hospital with hopes of starting a dialogue about mental health and the institution’s responsibility to do right by its patients. While some accused him of “setting back psychiatry 25 years” with his decision, Brooks saw the movie as an opportunity to shine a light on the realities facing patients rather than avoiding the conversation altogether. The film did just that and went on to be deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress in 1993.

Thankfully, as the world changed, so too did mental hospitals across the globe. Through advancements in technology and understanding of mental illnesses, the horror stories associated with these types of facilities became, mostly, a thing of the past. Things like lobotomies and mistreatment at an institutional level were done away with. Better medication, more refined treatment plans, and a sense of community became the norm for quite some time. The social stigma had evaporated, and treatment was readily available to any who needed it.

Unfortunately, the museum’s board does not feel this sense has continued into the modern era. Due to a lack of funding and a rise in government mistrust, those who seek and require treatment are often unable to access it. Most, if not all, patients currently residing at OSH have been charged or convicted of a crime – some even resorting to committing crimes as a means of receiving treatment. Once again, there has been an unfair stigma placed upon those who seek treatment. That said, the hospital’s vision has remained unchanged. “… Inspire hope, promote safety, and support recovery for all.”

For the most part, today’s patients are seen after facing “extraordinary events” – seeing something that others cannot see. Students learned that every patient’s event is treated as unique because the personal circumstances surrounding their needs are always different.Some events may be trauma responses, some may be drug-induced, and some may be mental issues that were inescapable from the moment they were born. Some religions and cultures even view these extraordinary events as blessings, and the people experiencing them feel great pride in the things they are able to see. Every single person who is being seen must be treated in a way that fits their specific needs.

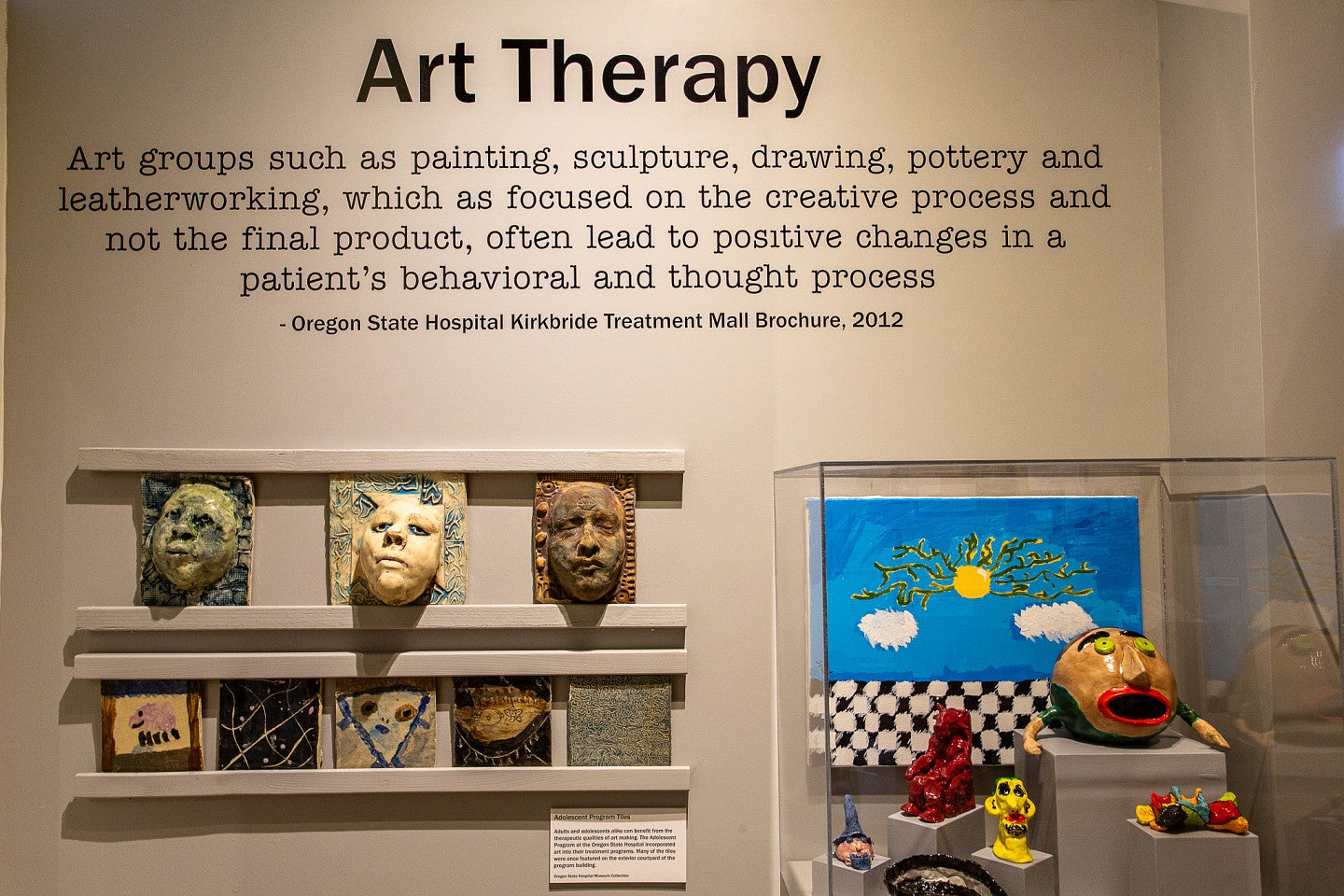

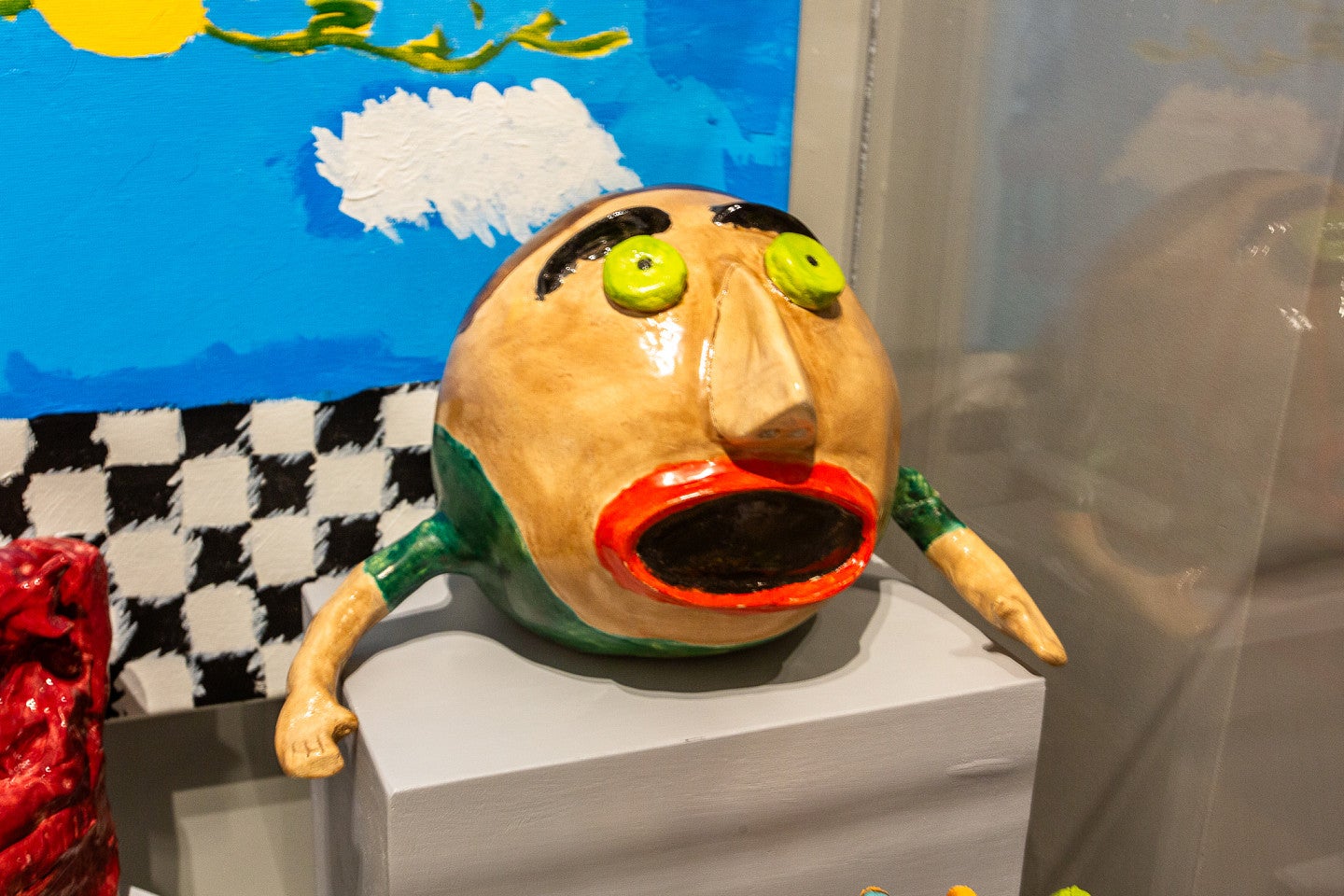

Many of OSH’s resident treatment plans include different forms of therapy. Patients have the opportunity to participate in art, music, occupational, industrial, and recreational therapy as a means to improve their mental and physical health while developing skills to give them independence. One of the many topics discussed in Art, Madness and Disability was the therapeutic and rehabilitative uses of the arts. At OSH, art therapy was a means to give patients an outlet to relax, play, and create. It even gives non-verbal patients a medium to communicate their thoughts, interests, and ideas. Students were able to see many of the creations by former patients first-hand, seen below.

Aside from the rooms used by the museum, the State Hospital uses many of the original structures to this day to serve patients facing mental crises. There have been additional wings and sections built, and many remodels and restorations added to the building, but the original structures created in 1883 remain fully functional and are utilized daily. These beautiful, historic brick buildings stand out amongst Salem’s surrounding architecture, but they were created with more than aesthetics in mind. Every aspect of the structures comprising the hospital was designed with the idea of “moral harmony” in mind. The designs of the gardens and playgrounds, and even the placement of the patients’ windows were all purposely made to better serve the patients of the facility.

After touring the museum, Recreation Therapist and OSH board member Mike Patton took the group to the OSH Memorial, which sits a few hundred feet south of the museum. The memorial houses the unclaimed cremains of 3,432 people who died between 1913 and 1971, including 3,420 patients, five state employees, six infants, and one Salem community member. The copper urns visible inside the glass section of the memorial have faced corrosion due to their exposure to groundwater from several previous incidents. The reactions between the copper, groundwater, and cremains created unique, natural turquoise streaks and markings on each of the urns creating, in a sense, art out of life itself – a beautiful, poignant reminder of those lives lost to struggles with mental diseases.

Today, the OSH Museum of Mental Health is currently run by volunteers and supported by the generous donations of community members and competitive grants. The 2,500-square-foot museum includes permanent and changing exhibits to tell the history and constantly evolving present and future of the Oregon State Hospital.

Admission is $7 per person, $6 for seniors and students (with a Student ID), and free for members and children 10 and under. The museum’s hours are Thursday through Saturday from 12 to 4 p.m.