A proposed design from Robert Clarke's office, R A L X, that reenvisioned the Frank Lloyd Wright "Hollyhock House" as a home with ornamentation and style elements derived from LA urban culture with various icon graphics, such as bandana prints, to create a type of positive projection of appropriation. Image courtesy of Robert Clarke.

Throughout the history of the world, many cultures and people have manifested different ways of expressing their cultures and traditions. Music, art, story, and other methods of expression allow communities to make their mark on the world and contribute to the cultural evolution of future generations. One of the longer-lasting methods of expression and geographic community identity is the creation of culturally specific architecture.

Especially in recent years, energy and care are directed toward preserving and building upon structures and styles from the past. Whether through historic preservation or architectural “dissection”, scholars are able to preserve and observe edifices from ages past, inspiring the next generation of architects and designers. However, this cultural expression has shockingly not manifested itself in a recognizable architectural style among the African American community. Black architects and scholars, like Visiting Professor and Design for Spatial Justice Fellow Robert Clarke, are looking to change this perception and unearth a buried history.

An interior of home from a studio class that is based on the works of Ernie Barnes and inspiration found in traditional Igbo housing. Image courtesy of Robert Clarke.

“If you go to the caves of Indonesia, France, or wherever [humans] first inhabited and marked our territory, you understand that architecture is really about marking identity and time and marking existence and histories. It allows a person to create a physical space that can mark the rituals and preserve the history and identity of a group of people or community,” explained Clarke. “And now I'm trying to do that in terms of Black identity and history in the North American context.”

Clarke’s spring talk and supporting publication, The Black Aesthetic and Black Architecture: UN-earthing the Black Aesthetic, are equal parts explanation and exploration promoting dissection and conversation about Black architecture, its absence from the predominant architectural discourse, how Clarke injects these considerations into his curriculum, and the creative outputs from those studio classes.

“The first half of the presentation was my personal work and my journey into the Black aesthetic,” said Clarke. “And then how my work and methodology then plays into how I teach and the research and experimentation that happens in my studio. I’ve been engaged with this line of thinking, the culturally specific way of practicing and creating architecture, since 2017 or 18 when I started to work in Shanghai.”

During the 2000s, China recruited international architects to help build its presence in the contemporary architecture scene, but there was a shift from international offices and design firms to more local firms, thanks to the work of 2012 Pritzker Architecture Prize-winning architect Wang Shu. Wang Shu, the founder of Amateur Architecture Studio, was interested in investigating and defining what it meant to be Chinese in the 21st century. His award-winning work and success would help push the government toward local firms, helping usher in younger offices, like architect Philip Yuan’s Archi Union, that would sustain the cultural movement in China to this day.

Clarke worked for a time with Yuan and Archi Union in Shanghai. Like other new architecture firms in China, Yuan was interested in trying to figure out what it was like to develop an aesthetic or new architecture that was linked to identity, history, and ritual that was strictly Chinese. Yuan’s exploration and theories energized Clarke and helped set him down a new design path.

“When I got back to the states and returned to my previous office at Gensler, I started to think about what it would be like to have a culturally specific architecture that speaks to the Black population in the Americas,” explained Clarke. “Around the [start] of COVID, I started to do a lot of experimentations and collaborations, including my first with an architect called Demar Matthews who gained a lot of acclaim with his thesis proposal out of Woodbury that specifically looked at a Black aesthetic.”

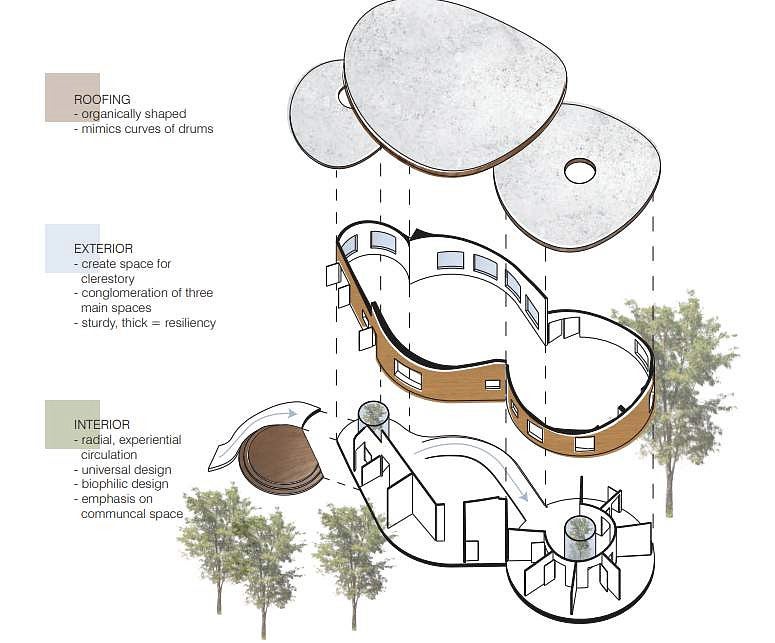

A studio class home design inspired by the Djembe. Image courtesy of Robert Clarke.

Clarke and Matthews would engage in competitions, executing and working with experimental ideas based on their explorations and, maybe controversial, ideas. They weren’t just winning the competitions, Clarke and Matthews were building connections with other experts and like-minded professionals to build on histories and journeys not known.

“[The competitions] allowed us to connect with people that have been working with the black aesthetic for decades, that their work has just haven't seen the type of acclaim it should have,” said Clarke. “Many architects and artists began to reach out to us to give the history on the black aesthetic, which probably spans back to the 70s or 80s.”

Individuals like 19-20 Design for Spatial Justice Fellow and University of Michigan Professor Craig Wilkins, Pratt School of Interior Design Professor and 2019 FIT Exhibiting Artist Jack Travis, and Kent State University Professor David Hughes are all seen as forefathers of this architectural movement and helped guide Clarke’s own explorations, especially true in the case of Clarke’s mentor Travis. Their published papers, pedagogy, and curriculum rooted in the exploration of the Black aesthetic helped Clarke and Matthews with their own development and pedagogy, enabling Clarke to create a unique perspective and subject matter for University of Oregon students.

“Anytime I come into an environment, I really try to connect with local histories and the people who are stewards of those types of history, such as former Design for Spatial Justice Fellows Kayin Davis and Cleo Davis,” explained Clarke. “I really try to intertwine [these individuals] in the class and ask for their opinions on the kind of direction of the studio and offer any edits to my syllabus. My studios are set up to be very open-ended, allowing for flexibility and the ability to pivot our direction to allow for certain realms of experimentation.”

The creative freedom and direction given to the students in Clarke’s studio classes is a change from the standard architectural classroom experience, and it shows through the unique projects submitted by his studio students.

An outdoor space developed in a studio class that blends Ethiopian and Black Mexican design elements to create a unique porch. Image courtesy of Robert Clarke.

“[The approach] is very non-mainstream to architectural education, so a lot of the students at first feel very off-kilter not getting a to-do list of how you do architecture,” said Clarke. “It's really about discovery and finding new ways, or old ways that have been buried, to express certain narratives and certain histories. Core architecture classes are really to build skill sets and the studios/verticals are supposed to open your eyes.”

Each class Clarke leads is a unique exploration for the cohort with the topic changing and evolving in real-time as new considerations from local community members can shape the class, creating an experience that is very specific to the time and place. Clarke’s hope for his classes and studios is that each continues to build upon the work of the previous generations of Black aesthetic scholars and architects.

“I'm definitely a person that's holding a torch [in this movement] and this is a very kind of collaborative experience where we talk with [other] architects constantly and we're all trying to kind of figure out this movement at this current time,” explained Clarke. “The work is built off of this constellation of stars that works to build up and define a language or movement that is specific to Black American culture. What will the continued continuum of this ideology look like in the next 100 years? ”

Clarke is the Wilson W. Smith III Visiting Faculty Fellow in Design for Spatial Justice and Visiting Assistant Professor in the College of Design’s School of Architecture & Environment. The Design for Spatial Justice Initiative was established in 2019 to support visiting faculty scholarship at the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, indigeneity, sexuality, and economic inequality that is enriched by their lived experience.

Six proposed column designs from a studio class. Image courtesy of Robert Clarke.