Tucked away in the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, in a small alcove embraced by four oil paintings, are two glass cases displaying five objects from the 14th through 16th centuries. Some museum-goers walk right past the cases, not realizing they’ve just bypassed the chance to see original works of art on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

These exquisitely detailed objects provide visitors insight into European history and belief systems from the late Middle Ages. They also present scholars with opportunities to understand how the items were used, the context of their creation, and the artistic skills required to create them.

“These objects represent a significant new teaching and research resource on campus, which is potentially useful for faculty in art, art history, medieval studies, religious studies, and other disciplines,” said Maile Hutterer, assistant professor in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture. “They are also beautiful objects in their own right.”

Above: On loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the objects now at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art reflect the diverse arts of Christian devotion and liturgy in Europe from the 14th through 16th centuries. All photos by Marti Gerdes.

Hutterer worked with Johanna Seasonwein, senior curator of Western art at the JSMA, to bring the objects to the UO museum on a two-year, renewable loan. Faculty from Romance languages, medieval studies, history, music, and elsewhere on campus have expressed interest in using the objects for class research.

For example, Hutterer is having students study the pieces in the art history course, “Divine Art,” that she and Akiko Walley, associate professor of art history, are co-teaching this term (winter 2017).

Above: Statues of the Virgin and Child were one of the most popular sculptural forms of the late Middle Ages. Unknown French artist, Seated Virgin and Child, 1300–25. Ivory, stain, 7 3/4 X 4 X 3 3/4 in.

“In the course, the objects not only serve as key examples for the representation of divinity in the Christian tradition. The students will also be asked to write short papers about these objects, which will help them develop the skills of close examination and visual analysis,” Hutterer said. Walley and Hutterer were awarded a Sherl K. Colman and Margaret E. Guitteau Teaching Professorship in the Humanities from the Oregon Humanities Center to develop the course.

In spring 2017, Hutterer’s Gothic Architecture class will “look at the objects, especially the censer and diptych, as examples of architectural representation in the Middle Ages,” she said. And in her Medieval Art class next year, she’ll ask students to write a formal analysis paper based on the objects.

“Having original objects on view is essential for this type of assignment because it allows the students to more fully grasp their materiality,” she said.

Assistant Professor Melissa Graboyes in Clark Honors College “brought her class on The Plague to the museum to look at the objects and talk about how people in the Middle Ages used objects as part of their prayers and devotion,” Seasonwein said.

The objects were also featured in the museum’s “Hidden Histories series,” which Seasonwein created at the JSMA for faculty and students “to delve into the deeper and sometimes surprising contexts of works of art on view in the permanent collection galleries.”

The objects on loan reflect the diverse arts of Christian devotion and liturgy in Europe in medieval Europe, as well as their creators’ priorities. The use of costly materials, such as ivory and gold-covered copper, glorified God and the saints. Some of the objects, such as the reliquary, were believed to give direct visual access to the divine. The copper container would have held a relic, such as a piece of bone, hair, or clothing, from a saint or holy person.

Support for the exhibit has been provided by the JSMA Academic Support Grant, the Department of the History of Art and Architecture, the Office of the Dean of the School of Architecture and Allied Arts, the Oregon Humanities Center, the Medieval Studies Program, the Giustina Professorship of Italian Languages and Literatures, and the Department of Romance Languages.

Above: The Virgin Mary holding her son was one of the most popular images produced by European sculptors in the 14th century. Mary’s crown, her jeweled brooch, and her elegant, swaying posture indicate that she is the Queen of Heaven. Her almond-shaped eyes and broad nose are common features of sculptures made in the region of Lorraine in eastern France. Unknown French artist, possibly from Lorraine, Virgin and Child, 14th century, limestone with traces of polychromy, 26 X 9 5/16 X7 1/16 in.

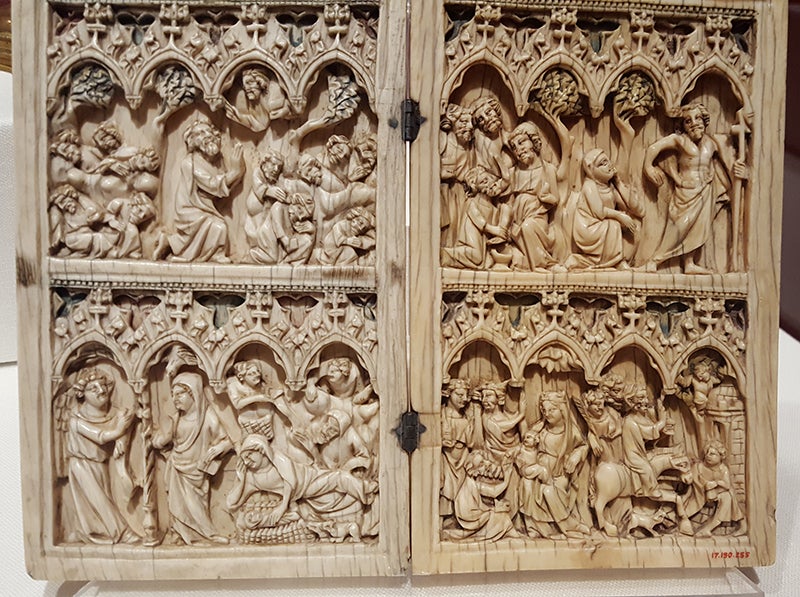

Above: The owner of the ivory diptych would have held it like a book, using the carved images to remember stories from Jesus’s life. Unknown French artist, Diptych with Scenes from the Life of Christ, 14th century. Ivory with traces of polychromy and metal mounts, 6 5/8 X 8 7/16 X 1/2 in.

Above: Shaped like a shrine or church, the censer would swing from its chain during religious processions, sending the smoke from the burning incense inside wafting out of the arched openings. Unknown Italian artist, Censer, 15th century. Copper-gilt, champlevé enamel, 8 3/4 X 4 7/16 in.