For Portland architect William (Bill) Hawkins III, preservation has been a career-long pursuit reaching back to when his great uncle met John Muir on a hike at Yosemite National Park. Hawkins’ devotion to Portland—from its natural amenities to its historically significant built environment—mirrors a family tradition of civic involvement that stretches back to his great uncle.

“My great uncle Lester Leander Hawkins was one of the people who brought J.C. Olmsted to Portland to supply Portland with its first parks plan,” Hawkins says. “Preservation became a big movement, with more and more people wanting to see the country do the right thing.”

“My great uncle Lester Leander Hawkins was one of the people who brought J.C. Olmsted to Portland to supply Portland with its first parks plan,” Hawkins says. “Preservation became a big movement, with more and more people wanting to see the country do the right thing.”

By doing “the right thing,” Hawkins means “providing the public with remarkable spaces.” It’s due to this ethic and his legacy of accomplishments that Hawkins was named the 2013 recipient of the George McMath Award, presented by the University of Oregon’s Historic Preservation Program and Venerable, Inc., for outstanding dedication to preservation. This year’s awards ceremony is May 15 in Portland. Tickets to the award luncheon are $50; the reservation deadline is May 3. The award honors the late George McMath, Oregon’s “Father of Preservation” and Hawkins’ business partner for three decades.

“Bill Hawkins' work with George McMath during the 1970s and ‘80s in Portland set high standards among the architectural profession for serious documentation, preservation, restoration, and adaptive reuse of heritage resources when others were still following Modernist avenues of design and planning,” said Kingston Heath, director of the Historic Preservation Program at UO.

“Bill Hawkins' work with George McMath during the 1970s and ‘80s in Portland set high standards among the architectural profession for serious documentation, preservation, restoration, and adaptive reuse of heritage resources when others were still following Modernist avenues of design and planning,” said Kingston Heath, director of the Historic Preservation Program at UO.

“Of particular significance were his efforts to secure remnants, and in some cases full cast-iron fronts, in the city from demolition,” Heath said. “Not only has Bill brought to national attention Portland's cast-iron front heritage, but also he continues to seek support from preservationists and architectural constituents to integrate that important collection into the Old Town urban context.”

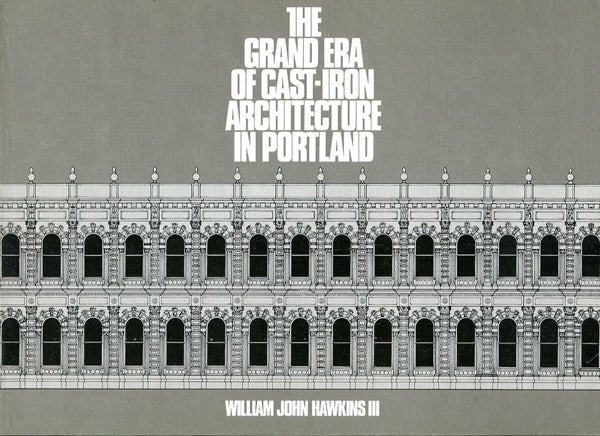

Hawkins, FAIA, has practiced architecture in Portland for 45 years, working from 1964-1994 with Allen, McMath & Hawkins and since 1994 in private practice. His work has focused on preservation and documentation of historic buildings and landscapes in Portland. He is also an accomplished author, including the books The Grand Era of Cast-Iron Architecture in Portland and Classic Houses of Portland, Oregon, 1850–1950. He is currently working on a book about the history of Portland’s parks.

His shift from traditional architectural practice to preservation was prompted by one moment, Hawkins says: “Meeting George” – as in George McMath. “At that time I was highly influenced by Louis Kahn, Paul Rudolph, and others,” Hawkins says. “That all changed in the ‘60s when I met George, which was a total delight. I volunteered to work on his book (A Century of Portland Architecture), and shortly after that I was asked to join the firm. I was with them 30 years or so. I left a little before George had a tragic stroke.”

Hawkins’ civic involvement includes his advocacy for the revitalization of Portland’s Skidmore/Old Town National Historic Landmark district and participation in organizations such as the Portland Historic Landmarks Commission, the State Advisory Committee for Historic Preservation, the Portland Parks Board, and the Bosco-Milligan Foundation. He holds a master’s degree from the Yale University Graduate School of Architecture, completed undergraduate work at Reed College, and was a Fulbright scholar in Rome.

Hawkins’ civic involvement includes his advocacy for the revitalization of Portland’s Skidmore/Old Town National Historic Landmark district and participation in organizations such as the Portland Historic Landmarks Commission, the State Advisory Committee for Historic Preservation, the Portland Parks Board, and the Bosco-Milligan Foundation. He holds a master’s degree from the Yale University Graduate School of Architecture, completed undergraduate work at Reed College, and was a Fulbright scholar in Rome.

Early in his career, Hawkins found himself connected to national advocates for preservation. In the 1970s, he met Margot Gayle, a well-known founder of New York Friends of Cast Iron Architecture, who was visiting Portland on behalf of her organization. “She gave me a copy of her book and invited me to New York to see what they were doing, and I decided Portland needed a chapter” of Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture. So he started one.

“George was working feverishly at the time to nominate the Skidmore District as a National Historic Landmark, the main emphasis being the uniqueness of Portland’s cast iron architecture,” Hawkins says. “Portland had been at center of cast iron architecture because it was founded in the 1840s when cast iron was the building material due to its being fireproof, so we had one of the unique cities in the country that was all cast iron. The East Coast had some areas here and there but not an entire city, and San Francisco had lost all theirs in the earthquake and fire. We thought that if Portland were to reconstruct what it had, it would be a significant cultural feature of the city. We had 12 years of great fun buying artifacts. The arches of the New Market Square and Ankheny Square were all restored by Friends of Cast Iron. The Skidmore arch was the biggest success; the Portland Development Commission put it back on the original site.”

His affinity for cast iron architecture also has a family connection. “The first cast-iron-fronted building in Portland was 1853. The ironwork was made in San Francisco by Jonathan Kittredge, my great-grandfather, a ’49r, in his foundry (The Phoenix Foundry), which supplied iron for buildings all over the West Coast,” Hawkins says. “By the 1860s, Portland started producing cast iron in its own foundries. That’s what my book (The Grand Era of Cast-Iron Architecture in Portland and Classic Houses of Portland, Oregon, 1850–1950) is about.”

Over time, Hawkins and McMath became known for restorations in Portland including The Old Church, the Jacob Kamm House, and the Pioneer Courthouse, among many others.

Hawkins credits McMath for the firm’s initial focus on preservation. “There weren’t very many people in Portland interested in preservation when George began advocating for it – he knew the most, was the fiercest fighter for it,” Hawkins says.

“We were consultants on the New Market Theater. It was pure fun to draw that beautiful façade, and the pleasure of seeing those arches go back to their original place was wonderful. The Old Church was an immense satisfaction as well. George was on one of the first boards for the Old Church; he pushed and pushed in the early, very difficult days, to get the board established. After his term ended, I was on the board and we continued restoration. Jerry Boscoe and Ben Mulligan had saved original parts, so we reconstructed the porte cochère, a very pleasurable historic preservation project.”

“We were consultants on the New Market Theater. It was pure fun to draw that beautiful façade, and the pleasure of seeing those arches go back to their original place was wonderful. The Old Church was an immense satisfaction as well. George was on one of the first boards for the Old Church; he pushed and pushed in the early, very difficult days, to get the board established. After his term ended, I was on the board and we continued restoration. Jerry Boscoe and Ben Mulligan had saved original parts, so we reconstructed the porte cochère, a very pleasurable historic preservation project.”

The firm’s projects ranged from individual sites to districts. “One of the most demanding projects we did was the 21 houses of Officers Row (in Vancouver, Washington),” Hawkins says. “George got that project. The buildings were derelict so we had to decide how to make them useful and restore them so they became Vancouver’s historic district.”

As for Hawkins’ later focus on landscape preservation, he points to his family legacy. “My great uncle, who knew John C. Olmsted, was my main reason for my becoming interested in parks – he led me into it,” Hawkins says. “My family kept boxes of his stuff – sketches, maps, drawings, proposals for parks, newspaper articles, histories – everything he did to help parks get started. I finally realized it’s a little treasure. So that’s what my (new) book will talk about.”

Attention to landscape is essential in architecture, he says. “All architects are interested in landscape, or they should be,” he says. “Historically, you look at whoever did the building – the Greeks placed their temples so magnificently in the landscape that they became almost a religious experience. With the great English landscape architects, from the 18th century and on, there’s a great tradition of developing a landscape (as part of the building process) and that morphed into parks. The English parks were all private, but with advent of Olmsted they became, in our American society, available to all.

Attention to landscape is essential in architecture, he says. “All architects are interested in landscape, or they should be,” he says. “Historically, you look at whoever did the building – the Greeks placed their temples so magnificently in the landscape that they became almost a religious experience. With the great English landscape architects, from the 18th century and on, there’s a great tradition of developing a landscape (as part of the building process) and that morphed into parks. The English parks were all private, but with advent of Olmsted they became, in our American society, available to all.

“That’s been a very important part of the quality of our parks,” he continues, “that everybody deserves to experience these remarkable places like Yosemite, Glacier, the state parks. The people who founded Portland Parks were on the committee to get Mount Rainier and Crater Lake designated as national parks and that tradition has gone on – so we have all these wilderness areas, and it’s become a part of our culture and it’s absolutely fabulous. It’s a wonderful feat that so many volunteers provided the public with these remarkable spaces. I’m a hiker, and on a beautiful day, to find a wonderful spot in one of our parks is very enjoyable.”

Parks like Yosemite, Hawkins says, “have managed to find a compromise that keeps the integrity of the park, which is true of almost everything in historic preservation – you have to find a compromise that maintains what’s beautiful and make it available to the public.”

Because of his advocacy for Portland parks, Hawkins’ efforts in landscape preservation became known nationally and he was invited to serve on the National Association of Olmsted Parks (NAOP).

“His dedication to the parks of his native Portland, Oregon, and indeed to parks everywhere, has been an inspiration to all,” landscape historian and NAOP board member Ethan Carr says of Hawkins. “Bill has devoted much energy to compiling all the Olmsted firm plans for (Portland) as a basis for park preservation in a way that serves as a model for other communities. Bill’s commitment, good humor, and professional knowledge have been deeply appreciated at the National Association for Olmsted Parks. The McMath Award honor is richly deserved.”

The McMath Award is hardly the first recognition for Hawkins’ contributions to preservation in Oregon. In 2010, the Bosco-Milligan Foundation/Architectural Heritage Center established the William J. Hawkins III FAIA Internship in honor of Hawkins and his exemplary contributions to local historic preservation. The paid internship is funded with contributions from colleagues, clients, family, and friends with the hope of encouraging the next generation of historic preservationists to be inspired by Hawkins’ example.

Story by Marti Gerdes