Kayin Talton Davis and Cleo Davis bring Portland architecture students to the historica Mayo House for the (re)Building Cornerstones studio

Kayin Talton Davis and Cleo Davis bring Portland architecture students to the historica Mayo House for the (re)Building Cornerstones studio

“There has been so much harm from design communities,

whether it’s through intellectual theft or gentrification

and condos going up. There is this level of trust and respect

that has to be made for the community,"

—Cleo Davis

Sean “Hobbs” Waters, 14, recalls his grandmother telling him stories about growing up on Broadway Street in Albina, an historically Black neighborhood in northeast Portland.

“There used to be tunnels under Broadway. As a little girl, she used to play under there,” Hobbs told the College of Design. And, due to the historic systemic racism of the City of Portland’s redlining and “fight the blight” policies, his grandmother, like many Black residents, was forced to move out of her neighborhood decades ago.

Since 2019, Hobbs—the teenaged Portland-based dancer, artist, and entrepreneur—has shared stories like these with students in the School of Architecture & Environment’s (SAE) Portland Architecture program as part of the (re)Building Cornerstones architecture studios.

He also shares his visions to honor the historical and cultural heritage of the neighborhood and reimagine its future through placemaking and educational community programming, visions that include an arts plaza and green spaces.

Architecture student Jade Danek (standing, left) presents her design; Sean 'Hobbs' Waters (standing, center) looks on.

Architecture student Jade Danek (standing, left) presents her design; Sean 'Hobbs' Waters (standing, center) looks on.

Empowering Youth and Community to Reclaim Their Spaces

Portland artists and educators Kayin Talton Davis and Cleo Davis, who teach the studio as Visiting Professors of Practice, say youth are key to the goals of the studio:

- to establish, deepen, and expand connections with local residents in Albina while working as partners to uncover, understand, analyze, and build proposals that creatively address decades-long, systemic obstacles to the benefits of space and place put upon Black/African-American communities

- to develop proposals combining architecture and historic preservation grounded in community histories and policy research for three sites that are specifically tied to the Black community and its history in Portland: the Mayo House, a residential site focused on urban agriculture and midsized development, and the BESTRONG Hub (a residential community-based learning center formed as part of the Black Educational Achievement Movement—BEAM)

- to leverage Portland’s new residential infill legislation, positioning the studio work as part of a network of efforts and partners operating in Albina that include the Albina Vision Trust and the integrated architecture/urban design firm El Dorado, which will at times provide insights and commentary on the studio’s work as well as technical support

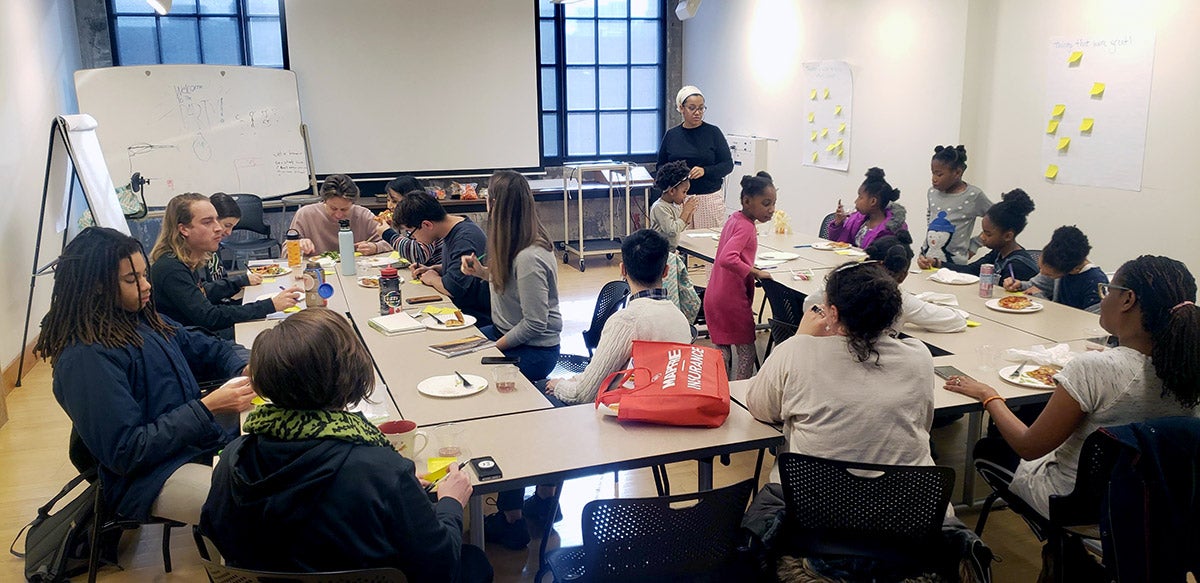

Cleo Davis (sitting, far right) and the (re)Building Cornerstones studio in Portland

Cleo Davis (sitting, far right) and the (re)Building Cornerstones studio in Portland

Learn more about the work of

(re)Building Cornerstones Faculty

"'Blightxploitation' seeks to

change the landscape of art

and civic engagement"

Regional Arts & Culture Council

"Public art on Williams Avenue

honors icons of Portland's historic

black community"

The Oregonian

"A tale of two creatives: Cleo

and Kayin Talton Davis"

The Skanner

"It’s Time for Architects to Accept

Responsibility" by Craig Wilkins

Curbed

"Karen Kubey on Spatial Justice

Through Social Housing"

NESS Magazine

“In creating and setting up this studio, we wanted to make sure we had community engagement, but, very specifically, working with youth,” said Kayin. The Davises have invited middle and high school students to the studio, as well as first-year college students. “So often we get caught up with: What is the academic thing to do and what are the points we need to hit without ever wondering about the why?” said Kayin. “Working with youth brings back some of that why. Why do we do this?”

Spatial Justice Lays Foundation for (re)Building Cornerstones

These studios are part of the Design for Spatial Justice Initiative (DSJI), a project launched in the School of Architecture & Environment in 2018. The Davises originally partnered with DSJI on (re)Building Cornerstones, an effort they began long before the architecture studio, in 2019, coteaching with then DSJI Fellow Karen Kubey. (Listen to the DSJI Podcast episode with the Davises and Kubey, “Rebuilding Cornerstones: Spatial Justice for Portland’s Black Diaspora”).

The studio is one of the efforts of the Portland Architecture program to collaborate directly with the community where it resides. In that same realm, the Historic Preservation department and its director Jim Buckley, as well as a team of faculty from across the college, have been doing community-engaged work in Albina, too, with the Albina African-American Cultural Heritage Conservation project.

Design for Spatial Justice Faculty Karen Kubey (left), Kayin Talton Davis (center), and Cleo Davis (right) outside the Mayo House

Design for Spatial Justice Faculty Karen Kubey (left), Kayin Talton Davis (center), and Cleo Davis (right) outside the Mayo House

The Davises designed this studio as an exercise of unlearning—many of the students they teach have been educated in the same systems that have propagated oppressive and racist policies, practices, and structures. But (re)Building Cornerstones is also about a multidisciplinary and entrepreneurial approach to working together, a process of repair, or as Kayin explains, the cultivation of Black joy.

“For me, it’s about creating those spaces for cultivating Black joy,” Kayin said. “So often there is not space to have that joy, whether it’s emotional space, personal space, or physical space. How do you grow it? How do you make something that brings peace, where you are not wondering about neighborhoods being racist or you’re not worried about the city taking away your home? Working within the realm of spatial justice—it leads directly to that.”

Beyond the Classroom: Investigating Oppression in Design and Policy

“The goal of (re)Building Cornerstones is to make a societal impact,” added Cleo. “In the long run the goal has been to take a look at how the built environment and natural environment, how academics, community and city infrastructure can help better cities and society as a whole. To investigate the oppressive formats that don’t allow for Blacks and other nonwhites to participate in building more prosperous environments.”

The Davises are also artists-in-residence at the City of Portland Archives, where they have researched the history of Portland’s Black community and brought architecture students in. Cleo has deep roots in the Albina neighborhood, and he wanted to trace them using the archives. In the 1980s, his family purchased a lot that included a seven-unit apartment building as well as a small house—the historic Mayo House, built in the 1890s. Through municipal policies such as “fight the blight,” the city forced a demolition of the apartment building, despite many attempts by the family to renovate it. (National Geographic recently featured the Davis family in the story, “Oregon once legally banned Black people. Has the state reconciled its racist past?”) In Cleo and Kayin's research, they found the property listed in the Cornerstones of Community: Buildings of Portland's African American History.

(Re)Building Cornerstones students at the City of Portland Archives

(Re)Building Cornerstones students at the City of Portland Archives

“What was exciting was we pulled the information data of the Mayo House from the archives,” Cleo said. “To see it on an administrative policy level versus having it happen to you was amazing and then to put it in the context of these waves of atrocities, of exploitation, and to know the policy behind it, was a whole other story.”

The Mayo House, in turn, originally sat at the corner of Sacramento Street and Union Avenue, and it was relocated twice before the Davises purchased it and moved it a third time in 2019 to 234 NE Sacramento St., as a way to highlight the disparity of historic preservation and the demolition of wealth-making opportunities within the Black community. The Mayo House will now become the ARTChives, a site to archive the Black diaspora—a cornerstone property for the Black community, creating a place of memory, research, advancement, and art.

Chocolate Cities and Rectifying Injustice

In fall term of 2020 and winter and spring terms of 2021, architect Craig Wilkins—also a DSJI fellow and Pietro Belluschi Distinguished Visiting Professor—has joined them in co-teaching.

“This is about trying to establish a real, deep, long-term connection in an area that has great historic value and cultural value, but it has not been treated fairly within the confines of the city,” said Wilkins. “The goal is to try to rectify that injustice, to situate the social and cultural value of that location with the economic value. This studio is focused on the idea of economic development and how that might be thought of through the eyes not of developers but the residents of Albina.”

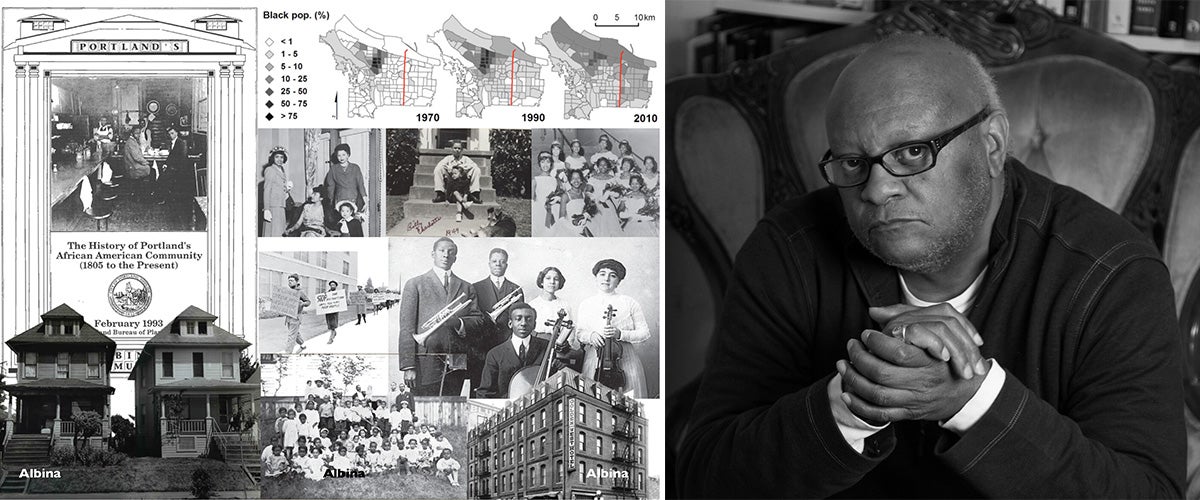

(Re)Building Cornerstones course materials and Design for Spatial Justice Fellow Craig Wilkins

(Re)Building Cornerstones course materials and Design for Spatial Justice Fellow Craig Wilkins

In the fall, Wilkins led the studio in their reading of Chocolate Cities: The Black Map of American Life. Chocolate Cities are defined as cities-within-cities, interconnected sites of Black migration and cultural production catalyzed by systemic spatial injustice. Some have remained intact while others have been demolished. Harlem, Nashville, Detroit’s Black Bottom, Seattle’s Central District, New Orleans’ Treme, and, of course, Albina, are some examples.

“Teaching Chocolate Cities is about getting students to realize that what is happening in Albina is not a unique experience,” Wilkins said. “What you see in Albina happened in Black Bottom in Detroit in the 1950s and in Atlanta today.”

For an earlier DSJI course, Portland architecture student Trayce Webb (MArch II, class of 2021), traveled in January 2020 with Wilkins and other students to Africatown, a Chocolate City in Alabama. In 2019, it was the site of the discovery of the last slave ship to arrive in the U.S.

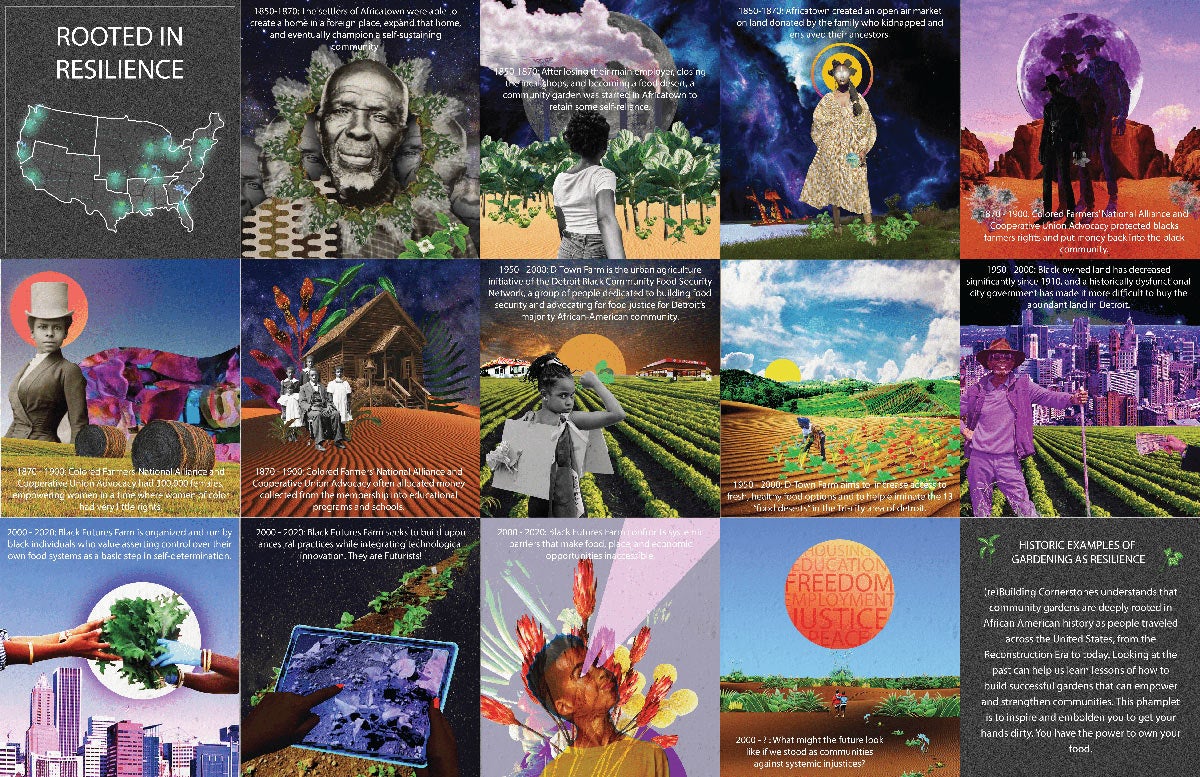

The 'Rooted in Resilience' project for (re)Building Cornerstone by architecture graduate students Trayce Webb, Katherine Marple, Madison Canelis, and Kelly Douglass

The 'Rooted in Resilience' project for (re)Building Cornerstone by architecture graduate students Trayce Webb, Katherine Marple, Madison Canelis, and Kelly Douglass

“We talked to a bunch of people who lived there about the degradation the paper mills caused to their homes,” Webb said. He said the class also talked to residents about their hopes to take back their neighborhood and build a community center.

Webb decided to take the (re)Building Cornerstones studio to continue to work with Wilkins.

“I’m really interested in issues of spatial equity and readdressing some of the systemic obstacles in our built environment,” Webb said.

The Unlearning of Academia and Earning Community Trust

In the studio, Webb has helped create community outreach tools to foster a dialogue with the Albina community and a community gardening kit, collaborating with Noni Causey, the executive director of the Black Educational Achievement Movement (BEAM), who is in the process of turning her Albina home into the BSTRONG Learning Hub. During spring term, the students are taking the input from the community and developing designs

BEAM Executive Director Noni Causey (standing, center) speaks to the architecture studio

BEAM Executive Director Noni Causey (standing, center) speaks to the architecture studio

“Usually, schools don’t push this type of learning. They kept pushing that this is really important to learn from the community,” Webb said. “Students usually don’t know how to have this dialogue with the community. It’s been eye-opening”

The Davises say one of the challenges of teaching, both youth and college students, is untraining them from the institutional educations that have helped created oppressive systems.

“How do you educate people within a system that was not built for people of color?” Kayin said. “How do you help them learn, to prevent them from recreating the system?”

"It’s about creating those spaces for cultivating Black joy,”

—Kayin Talton Davis

In one studio exercise, the Davises asked architecture students to write a narrative from the perspective of a Black middle school or high school student, from the perspective of the users or someone in the neighborhood who would utilize this space or structure. For many of the students, this was a challenge, which Kayin says was a necessary learning point for them.

The Davises have also pushed the architecture students to be more creative and liberated in their designs. Cleo Davis points to the “AfroLab” design that student Jade Danek created for the first studio with Karen Kubey (see the design below).

“You can bring your artistic capabilities to this. It doesn’t always have to look like an architectural presentation. The treatment that she did was outstanding,” Cleo Davis said.

The Davises said a lot of these exercises are an effort to start rebuilding trust between design professionals and communities of color.

“There has been so much harm from design communities, whether it’s through intellectual theft or gentrification and condos going up,” Cleo Davis said. “There is this level of trust and respect that has to be made for the community.”

Part of building that trust and respect is bringing youth into the fold and teaching them how to use their agency.

“We should be part of the process of planning,”

—Sean 'Hobbs' Waters

Hobbs, who is a mentee of Cleo Davis, also read Chocolate Cities. Together, they have attended city planning meetings and studied ODOT proposals. Engaging with the studio, Hobbs says, has given him insight into the conversations architects, designers, and planners are having—conversations that youth and communities of color have not traditionally had access to. In addition to dancing, he’s now interested in pursuing a career in planning.

“A lot of times people feel like they can’t, so they don’t come into these spaces. Just do it. Find out where the meetings are happening,” Hobbs said. “We should be part of the process of planning.”

Kayin Talton Davis (standing, right) instructs the (re)Building Cornerstones studio

Kayin Talton Davis (standing, right) instructs the (re)Building Cornerstones studio