In the late 1600s, a wooden synagogue was erected in the small Polish town of Gwozdziec. By 1731, a wooden dome, or cupola, was inserted into the roof of the synagogue. Its ceiling was elaborately ornamented with colorful paintings of animals and zodiac symbols and came to be known as the “celestial canopy.”

The synagogue was destroyed when the town was burned during military action in World War I, but a similar wooden synagogue was constructed on the site.

During World War II, Nazi invaders destroyed the rebuilt synagogue, and most of the town’s Jewish residents were either killed by Nazi troops or sent to concentration camps.

During World War II, Nazi invaders destroyed the rebuilt synagogue, and most of the town’s Jewish residents were either killed by Nazi troops or sent to concentration camps.

Research conducted by Thomas Hubka, MArch ’72, has assisted artists and craftspeople in reconstructing the synagogue. It now stands again as a permanent installation at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews (POLIN), located in Warsaw, Poland. The museum was officially dedicated October 2014.

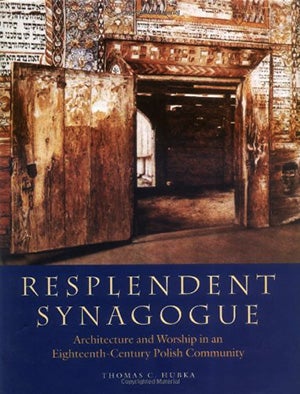

Hubka’s book Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community interprets the Gwozdziec synagogue within a Polish-Jewish context of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the ancestral home for 95 percent of American Jews. Resplendent Synagogue (Brandeis University Press and The University Press of New England, 2003) depicts “the spiritual heart of a once-vibrant Jewish community” through 150 historical photographs, architectural drawings, maps, diagrams, and color illustrations that survived in Polish archives. (A video of a lecture Hubka delivered at UO in 2012 discusses the synagogue project.)

UO architecture professor Howard Davis attended the museum’s grand opening in October for two reasons: to see the work from his colleague and old friend Hubka, and because of Davis’ great-grandmother, who was confined to the Warsaw ghetto where POLIN now stands. His great-grandmother was later sent to a concentration camp and died during the Holocaust.

“I thought, this is something,” said Davis. “This is a museum about the Polish Jews that a good friend had a hand in creating, and at the same time here’s my great-grandmother, who lived on this spot before she was sent away. These two things were converging, so I had to make the trip.”

Above: The intricate vernacular artwork is an 85 percent scale replica of the original synagogue, which weighs roughly 33,000 tons and covers 5,000 square yards. Photographs courtesy Thom Hubka.

The extensive documentation in Hubka’s book about the Gwozdziec synagogue assisted in the nearly full-scale reconstruction of the building, originally located sixty miles north of Gwozdziec in present-day Ukraine. POLIN chose to include the synagogue in the Warsaw museum because many Polish Jews would have attended the synagogue when it was in Ukraine.

Timber framers from Germany, Sweden, and America crafted the reconstructed synagogue’s roof and domed ceiling. The wooden construction was completely assembled at the Folk Architecture Museum in Sanok, Poland, then disassembled and held in storage for two years before being reassembled within POLIN. During the disassembly process, wooden boards from the ceiling's interior cupola were reassembled for painting workshops throughout Poland, where portions were painted, disassembled, and sent to Warsaw for final installation.

Handshouse Studio, a nonprofit educational organization in Norwell, Massachusetts, and run by professors at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, spearheaded the reconstruction. The complex carpentry and intricate vernacular artwork is an 85 percent scale replica of the original synagogue, which weighs roughly 33,000 tons and covers 5,000 square yards.

The grand opening ceremony of POLIN in October 2014 drew more than 1,500 guests, including Polish President Bronisław Komorowski, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, various ambassadors, and other foreign dignitaries.

“It’s remarkable—the wood construction and painting are really beautiful, and I was just stunned by the care and perfection in the craftsmanship,” said UO’s Howard Davis after attending the event.

Hubka described the moment of entering the museum and witnessing the synagogue’s installation as a “celebration of completion.”

Above: The interior design and especially the elaborate wall paintings inside the synagogue represent a distinctly Jewish tradition. This collaboration between Jewish and Christian builders, craftsmen, and artists in the creation of this magnificent wooden structure symbolizes an eighteenth-century period of relative prosperity and community welfare for the Jewish community of Gwozdziec.

Hubka noted that “I knew the synagogue thoroughly after fifteen years of intensive research. Still, walking into that space for the first time was startling, new, and exciting. I know every inch of this place. I know this better than anybody on Earth, I think. [Yet] it was a totally new experience.”

The synagogue’s reconstruction was deliberately installed without walls, which allows visitors to catch a glimpse of the roof from adjacent exhibits.

“The color and intensity of that dome is unlike any conception prior. Synagogues are generally not built that way,” Hubka said.

Hubka, whose family is Polish-Catholic, admitted that it’s unusual for a non-Jewish scholar to work on a subject like this.

“The history of Judaism embodies a scholarship of incredible depth and sophistication,” he said. “It was thrilling to think that I contributed a small part.”

The Resplendent Synagogue preface states: “So much has been written about the disunity and antagonism between [Christians and Jews] that it is sometimes hard to imagine a time of peaceful coexistence. Yet this book describes such a time when the wooden synagogue of Gwozdziec was built. This synagogue could not have been constructed without long periods of peaceful coexistence and mutual acceptance among the multi-ethnic and religious communities that lived in these small towns. This book was written about such an era.”

The Resplendent Synagogue preface states: “So much has been written about the disunity and antagonism between [Christians and Jews] that it is sometimes hard to imagine a time of peaceful coexistence. Yet this book describes such a time when the wooden synagogue of Gwozdziec was built. This synagogue could not have been constructed without long periods of peaceful coexistence and mutual acceptance among the multi-ethnic and religious communities that lived in these small towns. This book was written about such an era.”

The synagogue’s façade, Hubka demonstrates in the book, is largely the product of non-Jewish, regional architectural influences. However, the interior design and especially the elaborate wall paintings inside the synagogue represent a distinctly Jewish tradition. This collaboration between Jewish and Christian builders, craftsmen, and artists in the creation of this magnificent wooden structure symbolizes an eighteenth-century period of relative prosperity and community welfare for the Jewish community of Gwozdziec.

The massive reproduction from Handshouse Studio was teamwork among scores of volunteers, students, and expert carpenters in Poland, from other parts of Europe, and from America.

The replication project began in 2006. Several workshops were organized over a ten-year period, including architectural, painting, and woodworking. One of many workshops included a project to reassemble the synagogue's bimah, an eight-sided raised platform for the reading of the Torah that featured two staircases; it was a central fixture in the prayer hall. It contains ten-foot tall sides with panels adorned with lions, deer, and floral patterns and a spire reaching 16.5 feet in height.

Above: The replicated synagogue’s bimah is an eight-sided

raised platform with two staircases that was a central fixture in the prayer hall. It contains ten-foot tall sides with panels adorned with lions, deer, and floral patterns and a spire reaching 16.5 feet in height.

During 2011 and 2012, Handshouse Studio collaborated with the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute to recreate the synagogue’s roof. This involved students in “12 workshops in 8 cities throughout Poland and 58 professionals and 238 students from 26 American and 12 Polish universities,” according to the Handshouse website.

Hubka offered lectures about the Gwozdziec synagogue design, and the history of Jews and Poland to students, volunteers, architects, and carpenters involved in these workshops.

Handshouse Studio volunteers and founders Laura and Rick Brown had been discussing the recreation with Hubka since 2003, and spent ten years pursuing the project.

“This project would not have been a success without Tom’s scholarly research and his dedication to it,” says Laura Brown, director and cofounder of Handshouse Studio. “Tom has always been our scholar on the whole project because his book was a very significant reference. He’s been incredibly involved and supportive and willing to throw himself at the project.”

Every process in the replication relied upon eighteenth-century methods, raw materials, and tools. This approach offered an insight into engineering methods, pigment-mixing styles, and various challenges faced by architects, artists and builders centuries ago.

“They could have made the wooden members in plastic and spray-painted the paintings,” Hubka said. “They could have unofficially made this place. They didn’t have to consult [experts for the replication]. It is to the credit of the museum that they supported this historically accurate completion.”

The reconstruction project is the focus of the documentary “Raise the Roof” which premiered at the 2015 Atlanta Jewish Film Festival on February 3.

The replication of the synagogue provides the museum with a historical and cultural context for commonplace life in a Jewish shtetl and rewrites a chapter in Jewish and Polish architectural history.

“It’s the best intellectual work I think I’ve done,” Hubka said. “Writing this book took fifteen years with two years research in Poland, Ukraine, and two years research in Israel, and was easily the most challenging intellectual project I have ever taken.”

Hubka, who taught architecture at A&AA from 1972-1984, served as an architecture professor at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee before retiring in 2011 and moving to Portland, Oregon. He currently serves as adjunct instructor in the UO’s Historic Preservation Program.