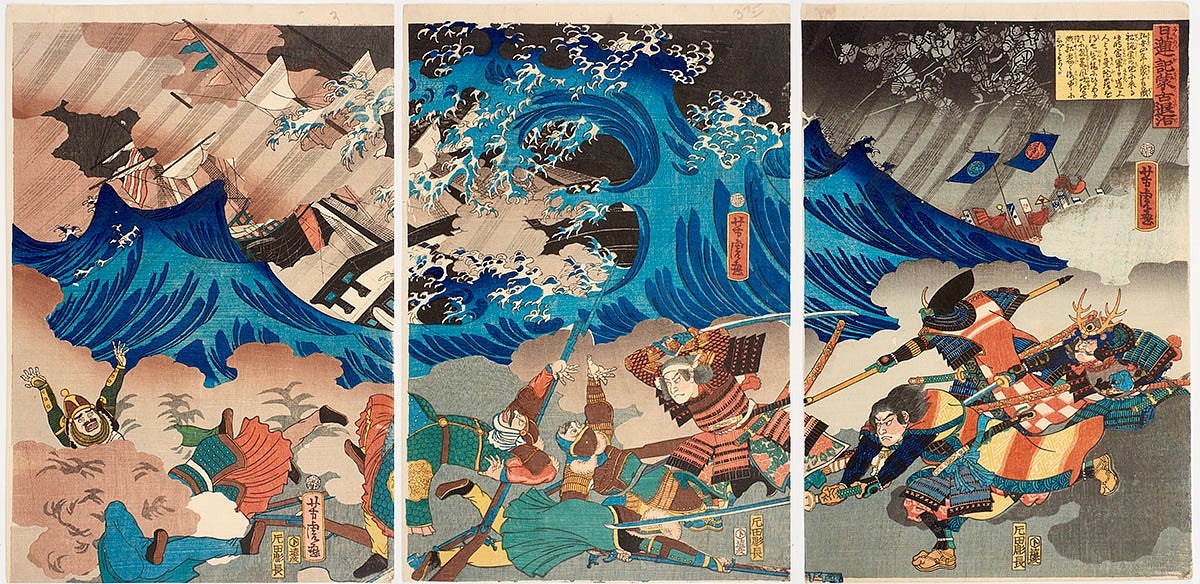

Water is ever present in the woodblock prints of the Utagawa School, the preeminent lineage of print designers during Japan’s Edo (1615–1868) and Meiji (1868–1912) periods. The element is captured in bright blues, from the brute force of waves in “The Chronicles of Nichiren: Expulsion of the Mongols” to the firefly-lit ponds of “Garden, Felicitation, and Beauty.”

“As a technology, water was harnessed, channeled both for domestic use and for industrial shipping lanes,” observed Emily Lawhead, a PhD student in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture (HAA). “Water also seeped its way into Edo mythology, where it emerged as ominous ghost-monsters and as a productive safety barrier between Japan and foreign realms.”

“They worked in groups to think of a dream exhibition that is grounded in the reality of exhibition planning within an art museum” —HAA Professor Akiko Walley

Lawhead’s research on Edo (current-day Tokyo) as the “city of water,” as well as dozens of prints depicting the life, popular culture, and landscapes of the period, are on view at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) in the exhibition Rhapsody in Blue and Red: Ukiyo-e Prints of the Utagawa School through July 17. See the JSMA website for updated visiting hours. The museum has also created a virtual exhibition.

Rhapsody in Blue and Red is the culmination of a winter 2019 HAA Japanese print class (ARH 488/588) team taught by Akiko Walley—the Maude I. Kerns Associate Professor of Japanese Art—and Anne Rose Kitagawa, the Chief Curator of Collections & Asian Art and Director of Academic Programs at the JSMA.

The course, which met regularly in the Gilkey Research Center at the museum, focused on Japanese prints from the private collection of JSMA benefactors Lee and Mary Jean Michels. The students, including Lawhead, were able to examine these artworks up close, conduct original research, and plan an exhibition.

“They worked in groups to think of a dream exhibition that is grounded in the reality of exhibition planning within an art museum,” Walley said. “This is one of many truly meaningful hands-on experiences that art history coursework can provide.”

“Giving students the opportunity to examine and discuss original works of art at length and in person and pulling back the museum ‘curtain’ to help them understand the process of incorporating what they’ve learned to conceptualize an exhibition are central to the core missions of the JSMA,” added Kitagawa. “The installations that result from such classes are always exciting, because they represent the cumulative knowledge, ideas, and efforts of a group of talented students choreographed by a professor and a curator.”

For one of the exhibition’s themes, Lawhead collaborated with fellow HAA PhD student Dan Baliban and Art History MA student Christin Newell to propose 15 Views of Water from the Utagawa School.

“We were interested in the diverse approaches to water in woodblock prints” Lawhead said. “We also wanted to explore the interconnected ways in which water was encountered in Edo-period life.”

Lawhead’s final paper on the topic, “Pictures of Sunbeams: Rethinking Photography and Meiji Woodblock Prints,” won the Laing Book Prize for Best Graduate Student Paper in Asian Art.

“Working face-to-face with the unframed prints made the viewing experience incredibly personal, and this had a tremendous impact on me” —Mac Coyle

Mac Coyle—then an Asian Studies MA student (class of 2021) who took the course and subsequently worked as a JSMA Laurel Curatorial Intern—said his group focused on showing various occupations of 19th-century Japan, selecting one of the works in the exhibition—"Sewing, Grooming, and Washing, from the series Seeds of Prosperity for Modern Ladies"—because it offered an interesting behind-the-scenes look at the domestic lives of women.

Coyle also contributed research to the label for “Once-Upon-A-Time Monsters Sugoroku.”

“This print is an Edo-era board game, which depicts a number of Japanese ghosts and monsters,” Coyle said. “Part of my final research for the class looked at how ghost stories in Japan’s northeastern region were represented in prints. It was so wonderful to see my ideas and contributions being used in the description of this print.”

The course also challenged students to consider practical aspects of exhibition planning such as working with donors and loans to fitting their dream exhibition into the physical reality of a specific gallery and finessing their arrangement of artworks and labels because of pragmatic constraints such as the presence of a wall vent.

“These are realities of working in a physical space, and it was great introductory training in museum work for the whole class,” Lawhead said.

Both Lawhead and Coyle said seeing the prints in-person and working collaboratively were the most impactful parts of the course.

“It was incredible to have such an opportunity to spend time with these artworks, ask questions, and closely examine the techniques and themes that were prevalent in the 19th century,” Lawhead explained.

“Working face-to-face with the unframed prints made the viewing experience incredibly personal, and this had a tremendous impact on me,” Coyle said. “It allowed me to see some of the finer details that went into producing these works, and really helped me connect to the class content in an exciting and personal way.”

What is your favorite print in Rhapsody in Blue and Red?

Coyle: This is such a difficult question! Working with the prints so closely, it’s really easy to get attached to them and there are a few that I have really grown fond of. One print that really stood out to me is “The Chronicles of Nichiren: Expulsion of the Mongols” because of its historical significance and allusions. The print was made in 1863, shortly after American and European powers began opening their own international trade ports in Japan. I find it really intriguing and clever how the creator of this print, Utagawa Yoshitora, likens the new American and European presence in Japan to the Mongol invasions of the late 1200s by adding in American flags and ships in the background, giving a cheeky nod and critique of his times in his historical subject matter.

Lawhead: My favorite print in the exhibition is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “New Yoshiwara”, circa 1831. I am very interested in depictions of light and shadow in these prints, and “New Yoshiwara” features a brilliant halo of moonlight over a path. This depiction of light, and the shadows on the figures below, are clear departures from traditional Japanese pictorial modes. In my final paper for the class, I argued that this shift was influenced by the availability of Dutch etchings and books, the introduction of the camera obscura and telescope, and other technologies that were reframing how light was understood and depicted.

Kitagawa: There are too many amazing prints in the Michels’ collection to choose a favorite! Beyond the stunningly beautiful landscapes of Hiroshige and his followers, I am always charmed by the whimsical nature of some ukiyo-e, such as Utagawa Yoshiiku’s delightful image of a “Bookstore, from the series Souvenirs of Edo,” which playfully advertises various real products available for sale by the publisher, including the print itself (seen hanging at far left). Such images express so much about the witty, street-smart spirit of Edo’s urban print culture.

Walley: In addition to their superb collection of works by those who are still famous, the Michels pursue designers who were preeminent during their time but are underappreciated today. One example is Utagawa Hirokage. We know very little about him except that he was a student of Hiroshige. His “Sudden Rain at Ryōgoku” epitomizes the Edo wit and humor that lovingly subverts his mentor’s mega hit series, One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. The breadth and depth of the Michels’ collection is what made our expansive exploration into the Utagawa School possible.