The first four-syllable word Wilson Smith learned as a child was architecture. “My Mom saw that I was this kind of artist kid, and she said, ‘you should become an architect because architects make lots of money’,” Smith says. “I just think she didn’t want me to be a starving artist!”

With his vocation laid out for him since age five, it made perfect sense for Smith to attend the University of Oregon, which boasts one of the foremost architecture schools in the country.

Smith (BArch ’80) cites several key UO professors who made lasting impressions on him: Earl Moursund, and Professor Emeritus Don Genasci, who Smith worked alongside in London; and Otto Poticha, a professor of practice and current adjunct professor at the school. “I had my first design studio with Prof. Poticha, and he was the one who made me believe that I could actually do it more than anyone,” Smith says. “All three of these professors were incredibly inspiring,” he says.

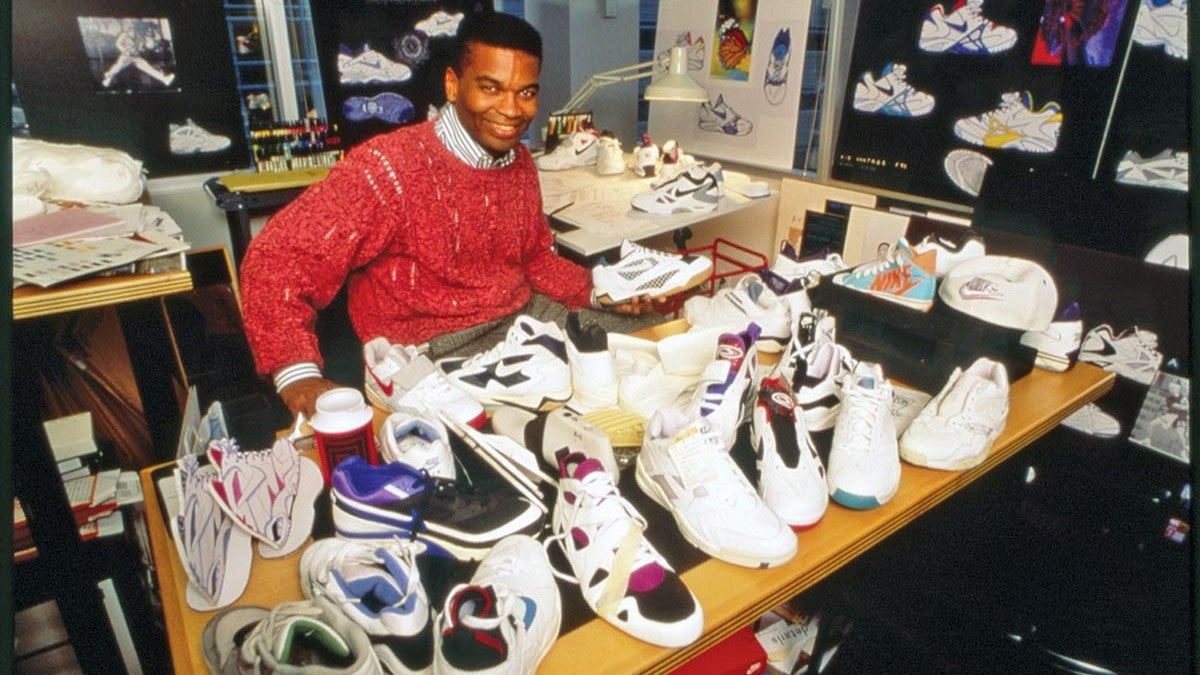

But it’s Tinker Hatfield (BArch ‘77), a fellow UO architecture alumnus, to whom Smith says he owes his career. Hired by Hatfield as an assistant in Nike’s corporate architecture department in 1983, Smith followed his mentor into footwear design, eventually becoming the creative force behind various tennis and basketball models.

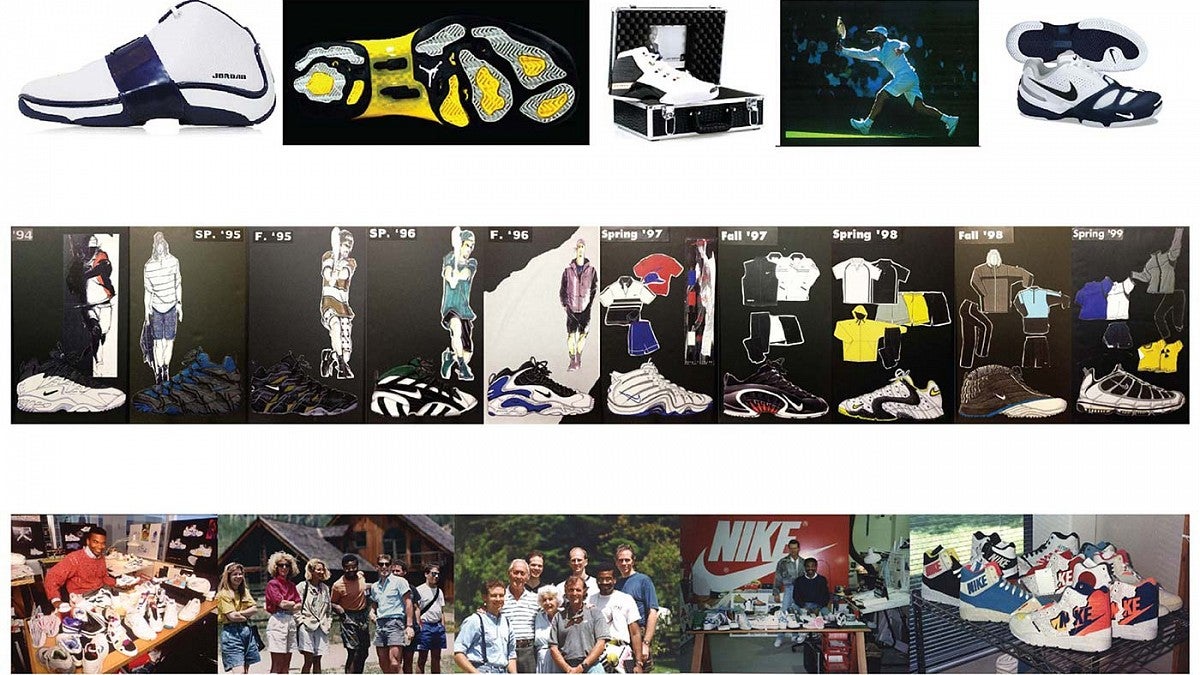

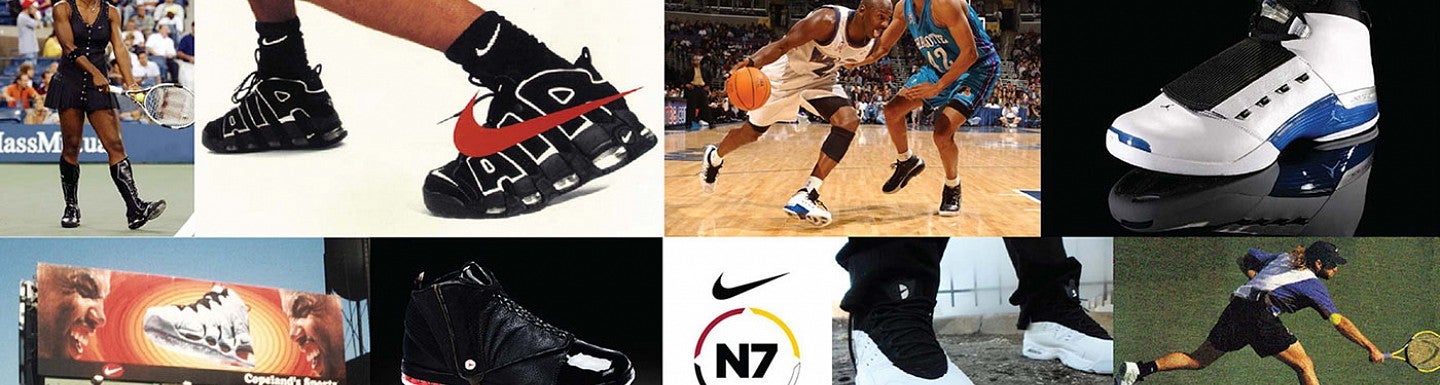

During his decades-long career at Nike, Smith, a senior designer and Nike DNA design specialist, has been involved in all aspects of design, from retail, graphics, and architecture to footwear and apparel. He designed and developed products for such high-profile athletes as Serena Williams, André Agassi, Roger Federer, and Michael Jordan, for whom he codesigned the Air Jordan XVI and XVII. Black Enterprise Magazine named Wilson one of America’s Top Black Designers.

“Whenever I see people wearing my product I feel overjoyed,” Smith says. “I think, ‘It’s a shoe.’ They could have worn anything. They chose one I designed. That’s a major honor. It’s also been a kick when the major athletes wear it. But even when other people on the street choose it, it’s a thrill.”

And now, Smith is stepping into his mentor’s shoes, so to speak, as this year’s recipient of the Ellis F. Lawrence Medal of Honor. Hatfield earned the award in 2008.

“Wilson is an exceptionally talented designer, teacher, and motivational speaker. We are thrilled to recognize his outstanding contributions to the field of design, and his passion for giving back to the next generation of designers,” said Christoph Lindner, dean of the College of Design.

Smith views the Lawrence Medal not only as an endorsement of his accomplishments but as an opportunity to have a much greater capacity to reinvest in the students at the UO. In addition to his work at Nike, Smith is an instructor in the UO’s Department of Product Design. “I really want to be about passing it on, empowering students to find their direction. That’s personally very huge for me,” he says. “I look at myself and the UO and I want to say, ‘hey, you can do it too.’ I got to hit a home run. The most important thing I can do is encourage the next generation that they can hit a home run as well.”

And as the first African-American recipient of the medal, Smith also hopes to encourage diversity in the design field. “I’ve been privileged as an African-American,” he says. “When I was at the UO there weren’t too many blacks in my class; there was maybe a couple of us. The diversity piece will only help design be for all people,” he says.

Indeed, a desire to make design more inclusive is at the core of Smith’s current foray into adaptive design, a concept that centers around designing equipment for athletes with physical disabilities. “As UO Architecture has been a leader in Sustainable Design, so UO Product Design engages the adaptive athlete with that same spirit,” says Smith. “Legendary UO track coach and Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman was inclusive of all people when he said, ‘if you have a body, you are an athlete.’ I love the robust invention, when designing for adaptive athletes. These concepts are often catalysts for more insight in all of the design world,” he adds.

Students in the program find ways to help athletes with physical impairments improve their performance. For instance, one student designed a special harness to help rugby wheelchair athlete Will Groulx to better leverage his body and movements during a game. Others looked for ways to help enable a woman who was born with one arm shorter than the other to participate in a triathlon. “We wanted to set up an equation that would give the students an opportunity to solve problems and work with end users to solve real issues,” Smith says. “Whenever they see someone who doesn’t have the same advantages, it motivates them to do some of their best work, so that’s been quite an exciting journey.”

As this year’s Lawrence medal winner, Wilson will be called upon to offer advice to graduating seniors at the College of Design’s Commencement ceremony. “My thoughts are that the older people should be about creating the channels for young people’s ideas to come forward, and I see myself as a channeler of great ideas,” Smith says. “I think design going forward is going to be more integrated with personal passions and with doing the right thing. Young people care about not only what you’re doing but why you’re doing it. That’s why I think empathy in design is an integral motivator to creating great stuff.”

“We need to be inclusive; we need to find solutions that engage all people and inspire them to do things that are empathy-driven from a much deeper place.”

Smith is also involved in Nike’s Better World projects, which include aiding recovery efforts in Haiti, and was the design director for N7, which brings the benefit of sports to Native American and First Nations communities in the US and Canada.

Above: Wilson Smith contemplates his next great shoe design at Nike in 1993.